Les Archives gaies du Québec sont heureuses de vous inviter en ligne pour voir la merveilleuse exposition HISTOIRES DE NOS VIES, qui témoigne de la vie des lesbiennes et des gais au Québec du dix-septième siècle à nos jours. Les 17 tableaux ont déjà été montrés lors d’expositions à Montréal, à Laval et à Québec. Chacun des tableaux de l’exposition regroupe des documents qui illustrent un incident historique ou une thématique de notre expérience collective. Procès pour sodomie en Nouvelle-France, scandale homosexuel en 1892 à Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, fondation d’un club littéraire gai et lesbien en 1917, mariage entre femmes en 1942 (!), manifestations suite aux descentes policières des années 1970-1980 : voilà quelques-unes des histoires qui vous seront racontées. Cliquez sur chacun d’eux pour voir en détail les contenus. Ils sont en format PDF.

Tableau 1

Tableau 1 Un tambour et trois soldats, 1648 et 1691

À peine six ans après la fondation de Ville-Marie, un jeune soldat est accusé du «pire des crimes.» Les Jésuites interviennent en sa faveur auprès des Sulpiciens, seigneurs de Montréal. Sa sentence, qui devait l'expédier aux galères, est commuée à condition qu'il devienne le premier bourreau de la Nouvelle-France...

Although there is no absolute identification of the drummer's crime, it has long been interpreted as sodomy, or some other sort of "unnatural" act. Church teaching since Thomas Aquinas had argued that sodomy was the worst of sins since it was most contrary to nature and therefore to reason. The drummer's partner is not identified, and what kind of sodomy he might have committed is not determinable from this brief reference. However since cases of bestiality were usually specifically identified, and other charges would more likely have been laid for an offense with a woman, we are fairly sure that this case involves homosexuality.

Directives for confessors published in New France by the colony's highest religious authority, the bishop of Québec, classified sodomy as a reserved sin which could only be forgiven by a bishop. Since there was only one bishop in New France, the Jesuits might have sought his transfer to the colony's religious and administrative capital for spiritual reasons. However their initiative is more likely an instance of old rivalries between religious orders, of Jesuit opposition to the excesses of piety of the Jansenist movement (here manifest in the repressive administration of the Montréal Sulpicians). As well, they could have been motivated by a differing perception of the gravity of the drummer's crime since French popular literature of the time frequently associated the Jesuits with sodomy.

In 1691 two soldiers and a lieutenant of the Company of the Marines were accused of the crime of sodomy. They were thrown into the bailiff's prison in Montreal while legal proceedings against them began. Witnesses and the accused were interrogated, but Lieutenant Nicolas Daussy de St-Michel obstinately refused to answer questions in spite of the threats of the prosecutor. Daussy did not recognize the authority of the bailiff and demanded to be judged by the Sovereign Council, even though the two soldiers, Forgeron, called La Rose, and Filion, called Dubois, had already confessed. The King's governor in Montreal recognized the justice of the officer's request and ordered the trial and the accused to be transferred to Quebec.

The Sovereign Council ordered that all the interrogations and proceedings be redone, noting that the Montreal trial had been invalid. From the deliberations of the Council, we may conclude that the crime had probably taken place in public, possibly in one of the numerous taverns of the city, since no less than eight witnesses are quoted. La Rose was sentenced to prison for two years and Dubois for three, while Daussy, held to be the instigator of the infamous crimes, was banished from the colony and ordered to pay two hundred livres to the poor as well as all the court costs. Considering that the prescribed punishment was burning at the stake, these sentences must be seen as relatively lenient.

But the most surprising aspect of the case was the aplomb with which Daussy initially refused any confession or collaboration. Perhaps he was aware of his legal rights and that his crime was a royal case which could not be tried in Montreal; this might mean he was aware of his legal status as a sodomite. Perhaps also he had served in France under one of the many homosexual marshals. In the army and the navy, love between men was considered a mere peccadillo, and men found guilty of it were even given sentences of military service. Condé, Gramont, Vendôme and Villars are but a few of the great captains who flaunted their tastes with impudence in the second half of the seventeenth century. Their soldiers mocked them in ribald songs, but often shared in their pleasures. Daussy, who had "debauched many men", was perhaps simply imitating his heroes.

Tableau 2

Tableau 2 Jonathas et David ou le triomphe de l'amitié, 1776

L'auteur, l'érudit jésuite Pierre Brumoy, se croit même obligé en son prologue de nous avertir qu'il s'agit ici de «L'Amitié tendre, Amitié sainte» et non de celle qui «réside dans les coeurs au crime soumis»; mais les soins qu'il prend ont plutôt pour effet d'éveiller nos soupçons....

In 1776, Fleury Mesplet, friend of Benjamin Franklin, fellow printer and admirer of the Philosophes, published Jonathas et David ou Le Triomphe de l'amitié, Jonathas and David or the Triumph of Friendship), a tragedy in three acts. This was the first, or perhaps the second, book ever printed in Montreal. The Biblical subject was one of the most popular themes for boys schools since it required no female roles. It is the story of the love "greater than the love of women" and the misfortunes of Jonathas, son of King Saul and heir to the throne of Israel, and the shepherd David, vanquisher of Goliath. Its publication was ordered by the Sulpicians who had it performed by their students at the Collège de Montréal, most likely at their August prize-giving ceremony.

Modern readers can scarcely believe how this play, which describes with charm and ardour a homoerotic passion, could have been innocently interpreted by both the actors and the public. Though we know that at that time the language of the purest friendship resembled the language of love, certain couplets must surely have moved the young actors and troubled their parents. The playwright, the erudite Jesuit Pierre Brumoy, felt obliged to write in his prologue that the relationship consisted of the "Tender Friendship, Holy Friendship" and not friendship that "dwells in hearts given over to crime." But the trouble he takes serve more to awaken our suspicions than to convince us that such ardent friendship could have been entirely pure. The declarations of love by the protagonists (whose names are carved on a tree!), the risks they take to meet, the sacrifices they make for one another, all may have seemed edifying examples for some while others judged them more suspect. Moreover the eighteenth century abounds in texts which, on the one hand, denounced the corrupting effects of theatre on youth, while others praise these amusing exercises that help the young to develop poise and the habit of public speaking.

No trace survives to suggest that the performance of Jonathas et David was greeted with controversy or condemnation. We do not know if other moral works like Le jeune homme à l'épreuve, Herménégilde martyr or Le jeune voluptueux were later performed at the Collège de Montréal. However local religious authorities had already shown their hostility to the theatre and it is not surprising that this tragedy is the only play Mesplet was to print.

Tableau 3

Tableau 3 Les apprentis, 1839

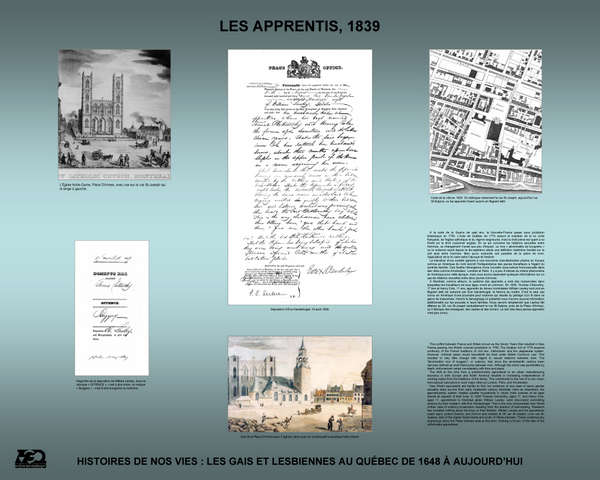

Carte de la ville en 1825. On distingue clairement la rue St-Joseph, aujourd’hui rue St-Sulpice, ou les apprentis furent surpris en flagrant délit....

The shift at this time from a predominantly agricultural to an urban manufacturing economy in both Europe and North America resulted in increasing independence of working males from the traditions of the family. This contributed to the rise of a new urban homosexual subculture in such major cities as London, Paris, and Amsterdam.

New World equivalents are harder to find, but evidence of one case of same gender sexuality does survive from early nineteenth century Montréal. Here as elsewhere, the apprenticeship system created parallel households in which male workers of all ages shared all aspects of their lives. In 1839 Thomas Clotworthy, aged 17, and Henry Cole, aged 11, apprenticed to Montréal gilder William Lawley, were discovered committing sodomy by their master's wife Eve Vanderboget. This is the only documented New World civilian case of sodomy prosecution resulting from the practice of bed-sharing. Research has revealed nothing about the boys or their families. William Lawley and his apprentices made signs, picture frames, and mirrors and resided at 29 rue St-Joseph, (now rue St-Sulpice, east of the Église Notre-Dame and south of Place d'armes). These contemporary engravings show the Place d'armes area at this time. Nothing is known of the fate of the unfortunate apprentices.

Tableau 4

Tableau 4 L'association nocturne, 1886

Hier soir, Clovis Villeneuve, un dude, affilié de cette association nocture, s'est approché d'un citoyen assis à cette heure sur les degrés du Champ-de-Mars, a engagé la causette d'une voix mielleuse et... s'est fait empoigner par Lafontaine, constable...

The site of important civic events and public celebrations, the Champs-de-Mars was also a fashionable place for an evening stroll. This description of men cruising among the poplars provides the earliest available evidence for gay social life in the city. Ominously, the story relates the arrest of Clovis Villeneuve through police entrapment.

The curious use of the Anglo-American word "dude" in this French-language news report is an interesting indication of the rapid spread of this neologism which seems to have originated in New York circa 1883, possibly deriving from "subdued". It was rapidly integrated into American usage as a term for young men "affecting an exaggerated fastidiousness in dress, speech and deportment". The cover of the New York humorous magazine Puck from 1883 further illustrates the popular conception of "dudes" as extravagantly dressed effeminate dandies.

Tableau 5

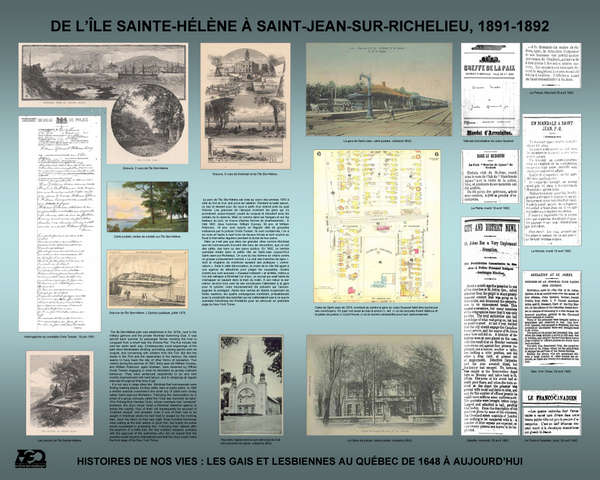

Tableau 5 De l'île Sainte-Hélène à Saint-Jean, 1891-1892

Les gravures de l’époque montrent les gens qui s'y promènent, pique-niquent, jouent au croquet et discutent avec les soldats de la caserne. Mais ici comme dans les hangars et sur les bateaux du port, on trouve d'autres formes de divertissement...

It is not only in large cities like Montreal that homosexuals were finding meeting places, be they cafés, bars or public parks. In 1892 a terrible scandal overwhelms the small city of Saint-John (today called Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu). Following the denunciation by a priest of a group curiously called the “Club des manches de ligne” (The Fishing-Rod Handles Club), whose members had “unnatural” practices, the city’s mayor hired a Montreal detective agency to entrap the culprits. Four of them will subsequently be accused of “indecent assault” and arrested, even if one of them has to be caught in Montreal where he had tried to escape by the morning train. Upon his return on that very night, three hundred townsmen were waiting at the train station to lynch him, but luckily his police escort succeeded in protecting him. Following their release after the payment of a hefty bail, the four buddies escaped, probably with the approval of the authorities who did not expect that the scandal would become international and that the story would make the front page of the New York Times.

Tableau 6

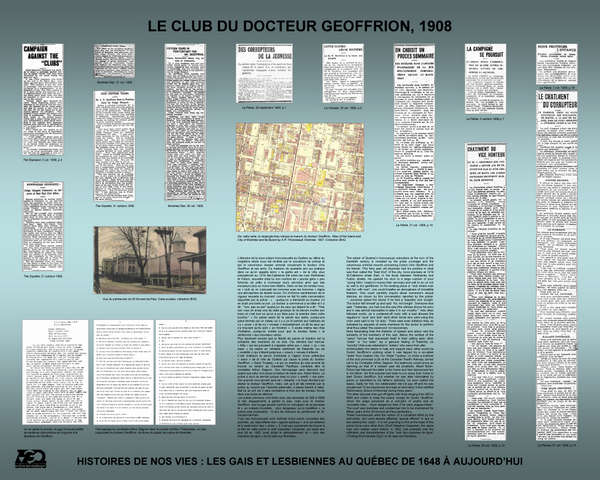

Tableau 6 Le club du docteur Geoffrion 1908

Ce médecin de quarante ans qui pratique dans ce qu’on appelle alors « la partie est » de la ville, plus précisément au 1219 Ste-Catherine Est entre les rues Parthenais et Fullum, accueille chez lui bon nombre de « jeunes gens » peu fortunés...

More fascinating than the freedom of speech and action was the solidarity of the members of this club. Below the surface of the “camp” humour that expressed itself in their calling each other “sister” or “my sister” lay a genuine feeling of fraternity (or “sorority”) that even extended to “sisters” who came from afar. Unfortunately this desire to help and support each other would be Doctor Geoffrion’s undoing when it was tapped by a so-called “sister” from Quebec City. For “Sister Trudeau”, to whom a member of the club promised a job at the Canadian Pacific Railway, turned out to be Constable Arthur Gagnon. His testimony would prove as damning as that of a sixteen year old prostitute, Albert Bonin.

Police had followed the latter to his home and had denounced him to his father. His first impulse had been to run away from home to alert Doctor Geoffrion, but whether he was later intimidated by police or submitted to his father’s authority, he soon spilled the beans. Sadly for him, his collaboration did not pay off and he was condemned “to be imprisoned and kept at hard labor in the certified Reformatory School of Montreal during three years.”

The other accused men got off lightly with fines ranging from $50 to $500 and orders to keep the peace, except for Doctor Geoffrion, whom the judge perceived as a corruptor of youths and an “incurable man… more dangerous than if he were plague-ridden.” The court was merciless and condemned him to be imprisoned for fifteen years at the St-Vincent-de-Paul penitentiary.

These homosexuals were the victims of a concerted effort by the authorities, who were already affecting “special officers” to spy on and destroy the “clubs”. It is not surprising to find at the head of this police force none other than Chief Detective Carpenter, the same man who sixteen years before, in 1892, had presided over the infiltration and dismantlement of the “club des manches de ligne” (“Fishing-Rod Handles Club”) in St-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

Tableau 7

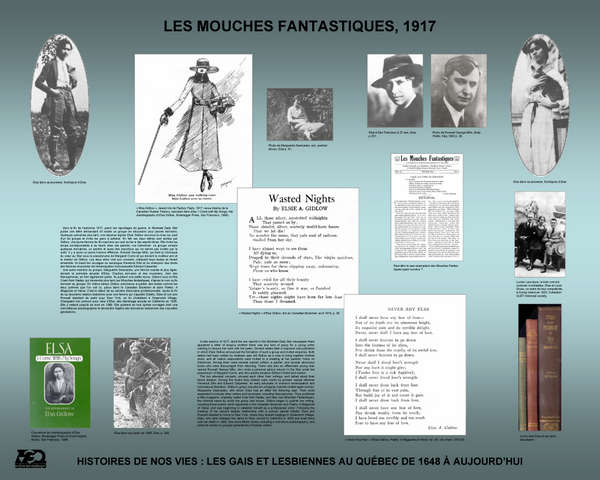

Tableau 7 Les mouches fantastiques, 1917

Vers la fin de l'automne 1917, parmi les reportages de guerre, le Montreal Daily Star publie une lettre demandant s'il existe un groupe de discussion pour jeunes écrivains. Quelques semaines plus tard, une réponse signée Elsie Gidlow annonce la mise sur pied d'un tel groupe et invite les gens à adhérer....

The two attended concerts, showed each other their writings, and talked about their future dreams. Among the books they shared were works by pioneer sexual reformer Havelock Ellis and Edward Carpenter, an early advocate of women's emancipation and homosexual liberation. Gidlow's group included an unhappily married middle-aged woman, Marguerite Desmarais, with whom Elsie had an affair the following year. Their circle expanded to include other writers and musicians, including francophones. They published a little magazine, originally called Coal from Hades, and later Les Mouches Fantastiques, the informal name by which the group was known. Gidlow began to publish her writing, including these poems which appeared in the Canadian Bookman and Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, and was beginning to establish herself as a professional writer. Following the breakup of her second lesbian relationship with a woman named Estelle, Elsie and Roswell decided to move to New York, where they shared lodgings in Greenwich Village. Elsie, who later changed her name to Elsa, moved to California in 1926 and lived there until her death in 1988. She wrote fifteen books, including a marvelous autobiography, and acted as mentor to younger generations of lesbian writers.

Tableau 8

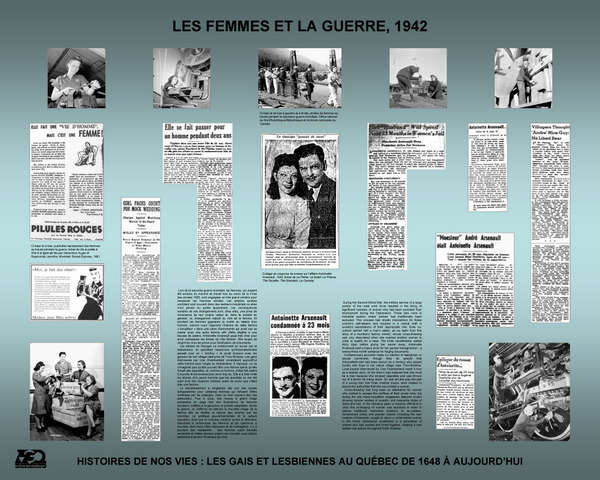

Tableau 8 Les femmes et la guerre, 1942

Et pourtant les femmes gagnaient la moitié du salaire d'un homme, comme nous l'apprend l'histoire de cette femme « travailleur » dans une usine d'armements qui avait osé se marier avec une autre femme afin d'être éligible à une hausse de salaire....

Contemporary accounts make no mention of lesbianism or sexual perversion, though they do specify that Antoinette/André had been known as a tomboy who played mostly with boys in her native village near Trois-Rivières. Local people interviewed by Line Chamberland recall it now as a lesbian story. At the time it was believed that she must be a man because she smoked cigarettes and was thrown out of a tavern for being drunk. So well did she play the part of a young man that three medical exams were needed to assure the authorities that she was indeed a woman.

Cross-dressing had long been an alternative for women who wished to escape the confines of their social roles, but during the war mass-circulation magazines featured covers showing women welders in overalls, and masculine styles of dress and hair. In the following years a massive offensive to undo this re-imaging of women was launched in order to restore traditional masculine positions to ex-soldiers. Government policy and popular culture, including the new medium of television, sought to return a re-feminized women to the home. Resistance crystallized in a generation of women who had worked and loved together, creating a new lesbian sub-culture throughout North America.

Tableau 9

Tableau 9 Montréal la nuit, 1920 à 1955

Des hommes gais fréquentent certains bars de la « Main » ainsi que ses cinémas tels le Midway et son voisin le Crystal, où des arrestations ont lieu dès 1929. Ces deux endroits resteront longtemps le théâtre d'activités sexuelles entre hommes et de harcèlement policier. Au Midway, dix-sept hommes sont arrêtés entre mai et septembre 1955....

Gay men frequented certain bars along the Main and as early as 1929 arrests were made in the cinemas such as the Midway and the adjoining Crystal. Both long remained sites for casual sexual encounters between men and police harassment was common. Seventeen men were arrested between May and September of 1955 in the Midway alone. The 1955 testimony of city lawyer Jacques Fournier before the Royal Commission on Criminal Sexual Psychopaths evidences the disdain the upholders of public morality held for these men who had no legal outlets for their sexual desire.

Montréal's nightlife was renowned throughout eastern North America in the 1940s and 50s. Among its most famous nightclubs was the Casa Loma on Ste-Catherine East, here illustrated by a photo of two unidentified patrons, an older man and his young friend and the cover in which the house photographer's work was presented. Some downtown clubs including the Copa Cabana are also shown. For gays, late forties nightlife focused on the Monarch Café east of the Main, and downtown clubs like the Hawaiian Lounge on Stanley and the Samovar on Peel. The Samovar was a mainstream club where, despite its mixed clientele, gay professionals felt at home thanks to the talents of its master of ceremonies, Carol (Carl) Grauer, himself gay. In the early 1950s the Samovar was transformed into the Downbeat Club, and its lounge section became the Tropical Club, Montréal's most famous gay nightspot in that decade. Gays also frequented the Kontiki bar across the street in the Mount Royal Hotel, where the gay customers discreetly gathered at the bar, while customers like the couple shown at a table were blithely unaware of anything out of the ordinary. A few restaurants in the Peel/Ste-Catherine area were favourite gay hangouts as well. These included the Diana Grill, and various branches of the Honey Dew chain. Cruising at the Peel Street Honey Dew, visible in one of these photos, was described in a McGill master's thesis on Montréal gay life written in 1954 by M. Leznoff.

Tableau 10

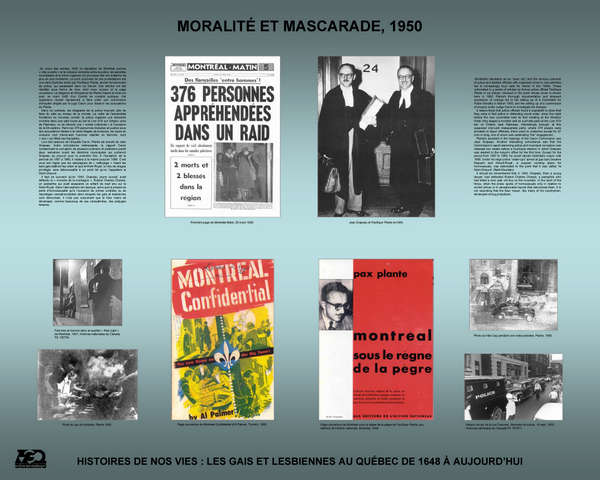

Tableau 10 Moralité et mascarade, 1950

Dans l’atmosphère de l’époque, alors que la presse ne parle d’homosexualité qu’à l’occasion de crimes sordides ou de reportages sensationnalistes dans lesquels les gais et les lesbiennes sont démonisés, il n’est pas surprenant que le futur maire ait développé, comme beaucoup de ses compatriotes, des préjugés tenaces...

It seems likely that police officials found it expedient to show that they were in fact active in defending moral order, since the night before the new committee held its first meeting at the Windsor Hotel, they staged a monster raid on a private party at the Lion d'Or bar on Ontario near Papineau. Interestingly enough, at this supposed mid-Lent masquerade party, where 376 people were arrested on liquor offenses, there were no costumes except for 37 men in drag, one of whom was celebrating "her" engagement...

Plante's assistant in the hearings of the Caron Commission was Jean Drapeau. Another interesting coincidence was that the Commission's report slamming police and municipal corruption was released two weeks before a municipal election in which Drapeau was elected to the mayor's office for the first time. Except for the period from 1957 to 1960, he would remain Montréal's mayor until 1986. Under his reign police “clean-ups” aimed at gay bars became frequent and Mount-Royal, a popular cruising place for homosexuals, was deforested to the point that it was called “le Mont-Chauve” (Bald-Mountain).

It should be remembered that in 1945, Drapeau, then a young lawyer, had defended Roland Charles Chassé, a pedophile who had killed a nine year old boy on the mountain. In the spirit of the times, when the press spoke of homosexuals only in relation to sordid crimes or in sensationalist reports that demonized them, it is not surprising that the futur mayor, like many of his countrymen, developed strong prejudices.

Tableau 11

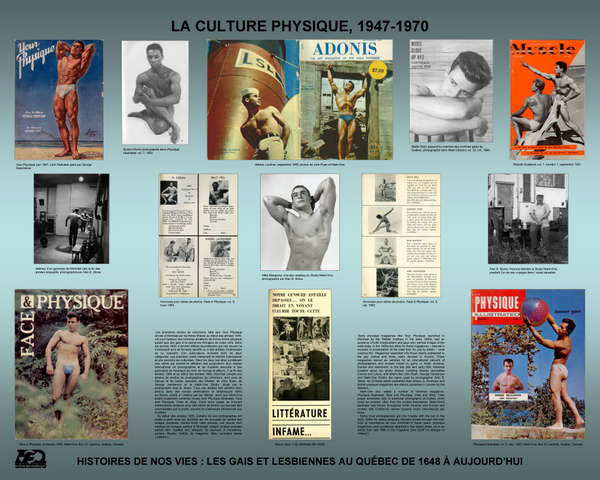

Tableau 11 La culture physique, 1947 à 1970

Au début des années 1960, certains de ces photographes ont maille à partir avec les autorités qui les accusent de vendre des images obscènes. Durant toute cette période, ces revues sont vendues en kiosque partout à Montréal, malgré qu'elles puissent parfois être sujettes aux attaques de journaux à sensations...

Mark-One also edited a number of Montreal magazines: Physique Illustrated, Face and Physique, Crew and Ahoy. Their pages advertised sets of additional photographs of models which could be ordered, often from the models themselves. Mark-One’s beefcake was known throughout North America and Europe and models with Québécois names became exotic international gay icons.

Some local photographers got into trouble with the law in the early 1960s for selling allegedly obscene photos through the mail. Sold at newsstands all over Montréal in these years, physique magazines were sometimes attacked in the sleazy press, as in an article from late 1964 in the magazine Zéro (itself no stranger to “infamy”).

Tableau 12

Tableau 12 Front de libération homosexuel (F.L.H.), 1970

En juin 1972, le groupe déménage dans un plus grand espace, coin Ste-Catherine et Sanguinet. Malheureusement, alors qu’ils pendent la crémaillère, la police fait une descente et quarante personnes sont conduites au poste central – on avait omis de se procurer un permis d’alcool pour l’occasion....

In Montreal, the magazine Mainmise spearheaded the diffusion of counter-cultural ideas, so it was not surprising that it was in its pages that gays published the call for a gay group here. The Front de libération homosexuel (FLH) began in the spring of 1971 and soon obtained an office on rue St-Denis where gays could drop in and talk, take part in group discussions and write comments in the log book (one page is shown here). During the following year they organized the city's first gay dances. In June 1972 the FLH moved into a larger space at the corner of Sanguinet and Ste-Catherine. Unfortunately the leaders failed to obtain a liquor permit for their housewarming party and 40 members were taken to police headquarters after a raid. The climate of fear was still strong enough for these arrests to kill the group, leading to a two year eclipse of the francophone gay movement.

There was nevertheless evidence of a new atmosphere at this time in the flourishing series of sexy tabloids like Omnibus and Ozomo and the publication of gay positive books like those of activist Jean Le Derff that appeared in 1973 and 1974. Mainmise continued to include significant gay content throughout its existence, going as far as to include a translation of the erotic Vancouver comic strip “Harold Hedd”.

Tableau 13

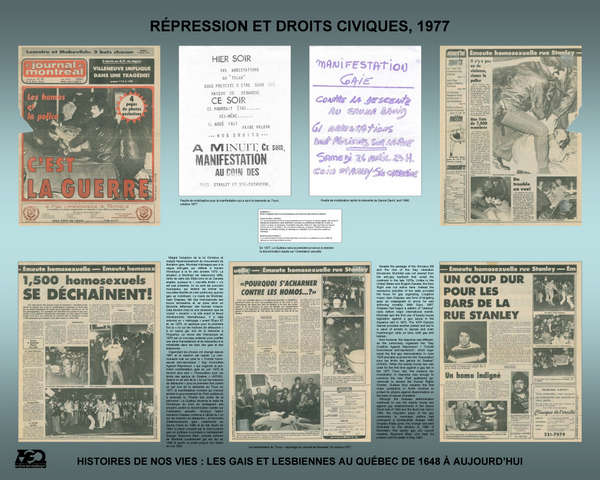

Tableau 13 Répression et droits civiques, 1977

Il a déjà ordonné un « nettoyage » avant l'Expo 67 et, en 1975, on applique pour la première fois la « loi sur les maisons de débauche » à un sauna gai, lors de la descente à l'Aquarius....

Now however, the response was different, as the community organized the "Gay Coalition Against Repression“ / "Comité homosexuel anti-répression", which organized the first gay demonstration in June 1976 and later evolved into the "Association pour les droits des gai(e)s du Québec" (ADGQ). When the bawdy house law was used for the first time against a gay bar in the 1977 Truxx raid, the massive demonstration in response was enough to convince the new Parti québécois government to amend the Human Rights Charter. Québec thus became the first major jurisdiction in North America to protect its citizens against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

Although the Drapeau administration continued to use the bawdy house law against gay establishments in the Sauna David raid of 1980 and the Bud's bar raid in 1984, the long-term place of the gay community in municipal politics had undergone a fundamental change. With Drapeau finally gone, this change was best illustrated by the election in 1986 of Montréal's first openly gay city council member, Raymond Blain, who kept his position until his death in May 1992.

Tableau 14

Tableau 14 Les lesbiennes s'organisent, 1970 à 1980

L'histoire lesbienne est parfois plus difficile à reconstituer que celle des gais. C'est sans doute parce que la sexualité et la vie sociale des lesbiennes s'expriment plutôt dans des cadres intimes et sont donc moins fréquemment sujettes à la répression policière....

For those who wish to avoid the commercialism of bars, community organized dances are a popular event.

Early lesbian organizing, outside of feminist groups, followed on the departure of women from the gay liberation group at McGill University in early 1973 to set up Montreal Gay Women. Some members of this group were involved in the publication of Long Time Coming, one of Canada's major lesbian magazines between 1973 and 1976. Francophone lesbians were active in these groups to some extent, especially in the lesbian conferences held here in 1974 and 1975. Coop Femmes, the first francophone group for lesbians, began in 1976. The first Montréal lesbian publications in French were Amazones d'hier, Lesbiennes d'aujourd'hui and Ça s'attrape, both of which began in 1982.

Tableau 15

Tableau 15 Le sexe, la mort et l'espoir – Les 25 ans du VIH/SIDA

Depuis l'été 1981 les Québécois, comme tous les humains, vivent avec la menace du sida. Ce qu'on appellera le Syndrome d'immunodéficience acquise fait son apparition sur la scène publique lorsqu'en juillet 1981...

1. First we remember the heavy loss of human lives for gays, their friends and families and everyone affected by this unprecedented crisis.

2. In 1981 the coming of AIDS opens a period of panic and confusion, followed by the first attempts at community response with the invention of "safer sex" and early fund-raising efforts, together with spontaneous measures to take care of sick friends.

3. This improvised effort expanded rapidly with the setting up of the first groups to work on prevention and care-giving such as C-SAM (Comité Sida-aide de Montréal) and the beginning of government response as well. This is the period when gays make common cause with Haitians, women and other affected groups as well as health professionals. After 1985-86, following the discovery of the retrovirus responsible, researchers create the first AIDS tests and the first medication that slows down the progress of infection.

4. When the 5th International AIDS Conference is held in Montreal in 1989, it opens a period of new militancy following the example of New York. Act-Up Montréal demonstrates at the opening of the conference and denounces the lack of financing for treatment and prevention by the Quebec and Canadian governments. This is also a period of broad recognition of social diversity and Quebec produces a number of prevention campaigns notable for their use of visual style and language adapted to specific populations including injecting drug users, Native people, and ethnic and racial minorities as well as segments of the gay community.

5. With the new treatments available starting in 1995-96, life changed dramatically for people infected. Despite the rigours of a difficult regime (many pills and very undesirable side effects), many people are able to resume their lives after a long descent, returning to work, to friends and to families. Quebec continues prevention work with specific populations.

6. Even so, in Montreal as elsewhere recent years have brought a new rise in infections among young men. People blame AIDS fatigue or the insouciance of the young who have never really seen those who are sick. Today the crisis is far from over. Around the world millions still wait for the new treatments. For us the greatest danger is to think it's all over and to relax our precautions. We are not out of the woods yet!

Tableau 16

Tableau 16 Un quartier pour qui? L’essor du village gai

Le Village continuera-t-il son développement fulgurant comme « centre-ville gai » du Québec? Disparaîtra-t-il quand ses habitants s’intégreront pleinement à la société québécoise? Ou bien la communauté gaie se déplacera-t-elle ailleurs dans la métropole comme d’autres communautés l’ont déjà fait?...

Tableau 17

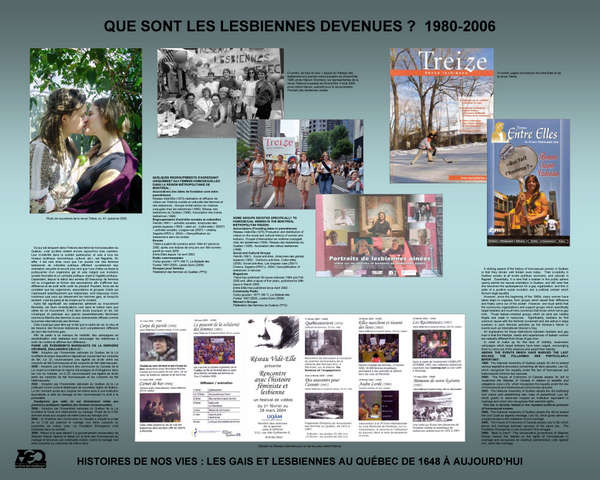

Tableau 17 Que sont les lesbiennes devenues? 1980 à 2006

Ce qui est éloquent dans l’histoire des lesbiennes du Québec, c’est qu’elles restent encore aujourd’hui bien cachées. Leur invisibilité dans la société québécoise, et cela à tous les niveaux (politique, économique, culturel, etc.), est flagrante....

However, since the beginning of the 1980s, many women have taken steps to organize, form groups which assert their difference and finally come out of the closet! However, one must admit that the community organizations and support groups which specifically target lesbians are much less numerous that those which serve gay men. Those lesbian-oriented groups which do exist are notably fragile and weak in resources. Significantly, lesbians do find common cause with the feminist movement and are active in large numbers in such feminist activities as the Women’s March or events such as International Women’s Day.

An explanation for these distinctions between lesbians and gay men is that the lifestyle, needs and experiences of lesbian women are radically different from those of gay men.

In order to make up for this lack of visibility, awareness campaigns which target lesbians have been waged, encouraging them to come out of the shadows and assert their identity.

AMONG THE EVENTS WHICH HAVE MARKED THE LAST DECADE, THE FOLLOWING ARE PARTICULARLY IMPORTANT:

1999 : The National Assembly of Québec adopts An Act to amend various legislative provisions concerning de facto spouses, Law 32, which recognizes the equality under the law of homosexual and heterosexual common-law spouses.

2000 : The House of Commons of Canada adopts An Act to modernize the Statutes of Canada in relation to benefits and obligations (Law c-23), which recognizes the equality under the law of homosexual and heterosexual common-law spouses.

2002 : The National Assembly of Québec adopts the Act instituting civil unions and establishing new rules of parenthood, Law 84, which grants to same-sex couples an institution equivalent to marriage and which also recognizes their parental rights.

This law is directly related to the repeated political pressure of homosexual women.

2004 : The National Assembly of Québec adopts the Act to amend the Civil Code as regards marriage, Law 59, which gives same-sex couples access to the institution of civil marriage.

2005 : The House of Commons of Canada adopts Law C-38, which allows civil marriage between spouses of the same sex. The Fondation Émergence is very involved in this struggle.

2006 : Back to zero? The conservative government of Stephen Harper renews the debate on the rights of homosexuals to marriage and announces an eventual parliamentary vote against civil, same-sex marriage.

SOME GROUPS DEVOTED SPECIFICALLY TO HOMOSEXUAL WOMEN IN THE MONTRÉAL METROPOLITAN REGION:

Associations (Founding dates in parentheses)

Réseau Vidé-Elle (1975) Production and distribution of videos on the social and cultural history of women and lesbians, Groupe d’intervention en violence conjugale chez les lesbiennes (1995), Réseau des lesbiennes du Québec (1996), Association des mères lesbiennes (1998)

Social and Cultural Groups

Femlib (1991): Social activities, Amazones des grands espaces (1993): Outdoors activities, Cultur-elles: (2005): Social activities, Les longues vues (200-?): Cinema, Sappho-GRIS (c. 2004): Demystification of lesbianism in schools

Magazines

Treize has published 58 issues between 1984 and Fall 2000 and, after a lapse of five years, published its 59th issue in March 2005.

Entre Elles has published since April 2002.

Community Radio

Funky gouine ( 19??-199 ?), La Ballade des Furies( 199?-2005), Lesbo-Sons (2006)

Women’s Groups

Fédération des femmes du Québec (FFQ)