Walls have Ears: The Stories of Montreal’s LGBTQ2S+ Spaces

Exhibit curated by V. Samoylenko

(fall 2021)

with added material by M. Daigle (summer 2021)

with added material by V. Samoylenko (winter 2022)

Introduction

Taking inspiration from queer mapping projects Queering the Map and Mapping Montreal's Queer Spaces , the project

The exhibit is a pilot project: it is a testament to what is possible to achieve in terms of public history exhibits even in pandemic conditions. Even with limited time, resources and spaces explored, the exhibit highlights the sometimes contradictory realities that exist or have existed for LGBTQ2S+ people. Like our own memory, the project combines multiple times and spaces in a simultaneous manner. Hopefully, the project will inspire larger and more elaborate projects combining oral history and mapping. As well, the project is designed to inspire greater collaboration between the Archives gaies du Québec queer archives across Canada and even worldwide.

In the summer of 2021, we had the pleasure of hosting a physical version of the exhibit on the pedestrian portion of Sainte-Catherine. Keeping in mind the accessibility of knowledge,

Montréal : ville gaie

The stories presented in this exhibit are those of seven narrators: Armando Perla (A.P.), Derek Vincent (D.V.), Pierre M. W. (P.M.W.), Ménélik Blackburn-Philip (M.B.P.), Mathilde Geromin (M.G.), kimura byol-nathalie lemoine (k-l.) and Michelle Wouters (M.W.). They talked about their experiences as LGBTQ2S+ people, as well as spaces that were important to them. Some of the participants were born here; others immigrated here because they felt that the city was more open towards LGBTQ2S+ folk.

The exhibit is subdivided by neighbourhoods to allow for historical context. Though some of the discussed spaces do not fall within the boundaries of the described neighbourhoods, they are nevertheless grouped by proximity for an easier browsing experience.

It is important to note that the exhibit focus on places which interview partners brought up in their interviews. In reality, many more existed. In addition, the transcriptions are kept in the language that the interviewees chose to speak.

To listen to the testimonies, click on the pin of your choice and press the play button. To consult the full photographs and their sources, click on the photograph of your choice.

A.P.: My cousin, who had, you know, the one who had told me initially in El Salvador that I would be able to come here if anything ever happens, she was living in Ottawa, and she would always say to me – she would always talk to me about Montreal. And she would say “oh, you need to go to Montreal” you know, “it’s so gay,” she’s like “you know I have friends, I have Salvadoran gay friends there.”

M.G. : Donc je suis arrivée, donc c’était en ’95 la première fois, tout le monde habitait sur le Plateau, dans des colocations évidemment. Et il y avait tellement, tellement d’homosexuel.le.s c’était génial [rire]. Et, en fait ce que j’aimais beaucoup, c’est qu’il y avait beaucoup d’homosexuel.le.s, beaucoup d’hétéros, et tout le monde se mélangeait, c’était pas un problème en fait. Voilà, c’était plus un problème pour personne. […] Dans ma tête, l’effet d’arriver à Montréal et de pouvoir vivre ça, sans que ce soit un problème, pas un problème pour personne … C’était – J’étais arrivée à la maison en fait.

k-l. : Ce que je me suis dit c’est de m’informer d’abord sur la situation ici à Montréal, par rapport aux homosexuel.le.s. C’est une des raisons pour laquelle je suis venu.e, parce que j’avais vécu beaucoup de discrimination en Corée.

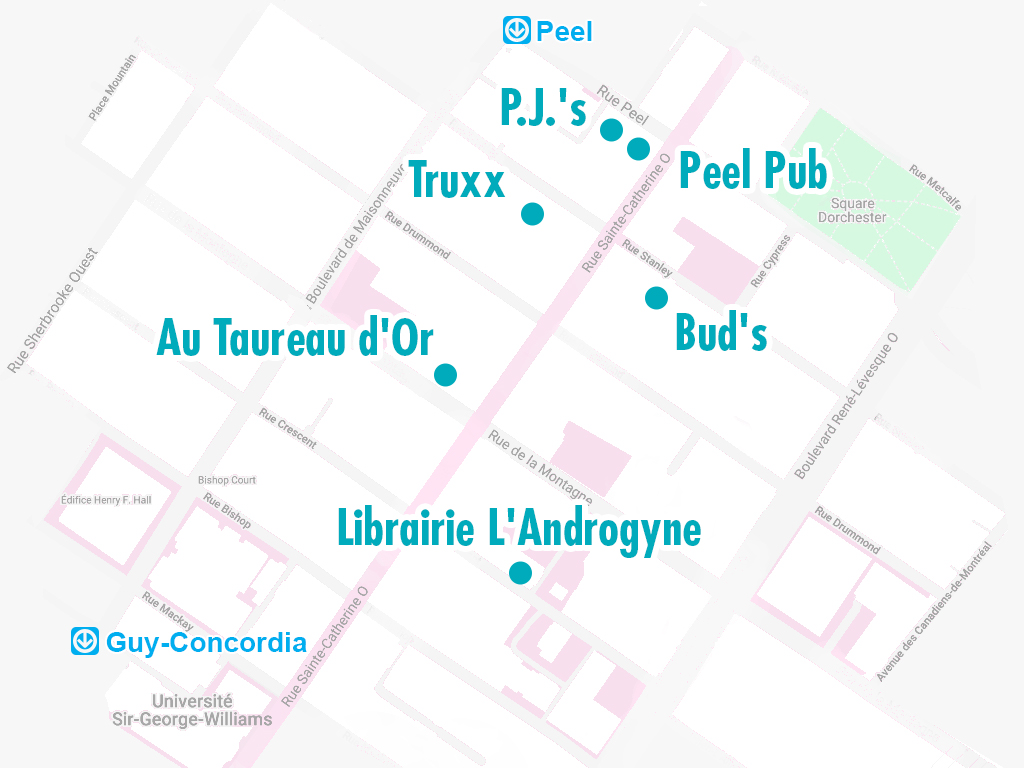

The West Village

Well before the current Gay Village of Montreal existed, Montreal’s gay neighbourhood was situated downtown. Centered around Peel and Stanley streets, and, at the time, offering affordable housing nearby, it was easily accessible to gay patrons. Downtown, however, was also a space sought after by real estate and the finance sector. The Jean Drapeau municipal administration (1954-1957, 1960-1986), wanted, on one hand, to make Montreal into an international, modern city, and on the other, to defend traditional morality. As such, the gay presence in Downtown Montreal became a problem for mayor Drapeau, both from an economic and a moral perspective.

The adoption of the Omnibus Bill 1969, decriminalizing homosexual relations between two consenting adults in a private setting, did not prevent police raids under the Drapeau administration. Instead, the authorities labelled gay bars as “bawdy houses” to justify arrests. Moreover, the federal legislation only decriminalized sexual relationship between adults in private spaces. As such, gays were harassed by police in public spaces.

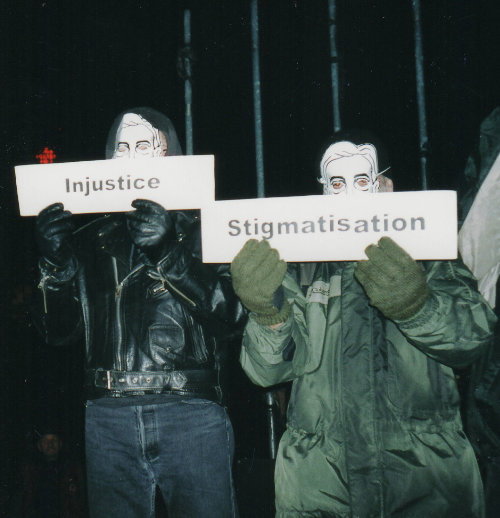

With the Olympic games of 1976, Jean Drapeau’s infamous “cleanup” of the city ushered in an intensification of police repression, not only against gays and lesbians, but also against sex workers. The raids continued after the Games. Notably, the raids on the Truxx and the Mystique on the 21st of October 1977 elicited an instant response on the part of the gay community. After this raid, the Association pour les droits des gai(e)s du Québec (ADGQ), a young organisation defending gay rights, mobilized the community and the following day, about 2000 people filled the streets to protest police abuses.

Adress : 1428, rue Stanley

(Police raid in 1977)

P.M.W. : Le Truxx, j’y allais mais moins, c’était – le Truxx c’était un petit peu plus disco, c’était les p’tits gars un peu plus preppy, un peu plus mode. Mais, pour danser, ça avait un charme […] la descente, j’étais pas là, c’est-à-dire j’allais au bar – quand je suis arrivé la descente avait lieu. J’ai vu effectivement des types, des flics monter comme des parachutistes […] ça faisait penser justement à des interventions policières de dictature. C’était vraiment exemplaire, on était absolument ahuris là, par le style de la descente, d’une, comment dire, une dramatisation, bah, à peu près comme les types que Trump envoie. On pouvait pas croire qu’à Montréal, une descente dans un bar gai, donne lieu à une telle mascarade, une telle farce. Ah non c’était inouï! [rire] Euh, j’sais pas costume de parachutiste, mitraillettes ou enfin fortement armés, les bottes de militaire et tout le truc – invraisemblable! Et effectivement le lendemain, c’était la première – c’était notre petit Stonewall.

Excerpt from Sortir de l’ombre :

« Le lendemain de l’intervention policière […], l’ADGQ décide d’organiser une riposte. Ce sont des moments fébriles. Nous sommes samedi. […] Une chaîne téléphonique est organisée dans la hâte; sept heures plus tard, la rue est à nous. Des tracts ont été imprimés et nous les distribuons dans les tavernes en début de soirée. Plusieurs bars refusent la distribution de nos feuillets à l’intérieur des établissements, mais nous sommes devant les portes pour prévenir ceux qui entrent. Vers 22h00, tout semble calme. […] Et très vite un miracle se produit : on est 20, on est 100. D’où viennent-ils ? Qui les pousse ? Quelle force vide les bars ? C’est une marée de chaleur, une vague à la fois en colère et joyeuse. On est 500, 1 000, peut-être plus. La rue Sainte-Catherine est bloquée, les policiers veulent dégager. On les conspue, on court, on crie; ils s’attaquent à ceux qui pendant quelques instants sont isolés. La rue est occupée, c’est l’émeute. Les télévisions sont là. On est 2 000. On a gagné. » -- Jean-Michel Sivry, in Sortir de l’ombre, pages 244-245

Adress : 1417, rue Drummond

(1967-1974)

The Taureau d’or is one of the many bars where John Banks worked. John Banks is the organiser of the first gay march in Montreal. For more information, the AGQ produced a documentary about John Banks in 2018.

P.M.W. : J’avais 22 ans, quand j’ai [rire], quand j’ai passé à l’acte d’aller dans un bar, en me disant que j’allais rencontrer. Et c’était justement Le Taureau d’or. Le Taureau d’or, où le barman était John Banks. […] Finalement c’était un bar étudiant. Les vieux étaient ailleurs, sur Stanley pis les vieux bars comme le 4 coins du monde, et quoi, le Hawaiian Lounge. D’autres noms me reviendront – et le Tropical ! Oui je pense le Tropical sur – où travaillait Armand Monroe. […] Le Taureau d’or n’était pas le genre d’endroit qui attirait les descentes. C’était l’endroit le plus nouveau, donc le plus nouvelle-vague, le plus contemporain et qui ne ressemblait pas à ce qu’on appelait les vieux bars de tapettes à l’époque.

Adress : 1107, rue Sainte-Catherine Ouest

(1958- now located at 1196, Peel street)

Opened in 1958, the Peel Pub was one of the many gay establishments of the West Village. Due to the climate of police repression, the Peel Pub enforced strict rules regarding the proximity between men.

P.M.W. : Les règlements étaient assez durs, et la taverne encore plus parce que c’était une taverne, là c’était carrément les waiters qui venaient nous engueuler ou nous foutaient à la porte. Je me rappelle d’ailleurs une fois à la blague de m’être assis sur les genoux de John Banks [rire] à la taverne au Peel Pub. Et, bah, pour rire là c’était pas du tout, c’était ni sexuel ni – c’était juste à la blague, et aussi un peu pour provoquer les waiters, les garçons. Et on m’avait mis à la porte, mais pas en me refusant de revenir là mais tsé l’avertissement était très sérieux. […]: Début 70, enfin toute la décennie, le Peel Pub était le lieu où on rencontrait tout le monde, et où on trouvait toujours un copain.

Adress : 1252, rue Stanley

(19??-1984)

The closing of the Bud’s not long after a police raid on the 2nd of June 1984, as the new Village at the East was starting to take off, often marks the end of the West Village.

P.M.W. : La nuit effectivement on sortait du Bud’s, qui était aussi un endroit que je fréquentais beaucoup, j’étais très versatile, et le Bud’s la nuit à une heure du matin, il y avait au moins une centaine de clients qui étaient dehors. On sortait même avec nos verres et on buvait sur la rue, en s’assoyant sur les autos, et c’était très le fun, ça faisait très new yorkais justement.

Adress : 1422, rue Peel

(1965-early 1980s)

1422 Peel street was once home to the Tropical Room and the Downbeat Club in 1952. The Tropical was a unique space, as it refused visibly heterosexual clients. Armand Monroe, who was the master of ceremonies and a drag artist at the Tropical Room, fought for gay men’s rights to dance together, which became possible for the first time in Montreal in 1957. In 1965, a criminal fire destroyed the establishment, but the PJ’s took its place, and Armand Monroe remained the M.C.. The cabaret was a place which offered many drag shows. Until the 1980s, the PJs remained a very popular place in the gay community.

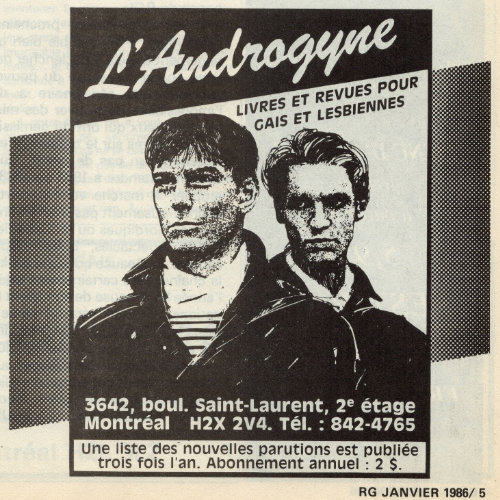

Adress : 1217, rue Crescent

(1973- 2002)

1217, Crescent street (1975-1982)

3636, Saint-Laurent boulevard (1982-2001)

1436, Atateken street (2001-2002)

Androgyny was the first gay and lesbian bookstore of Montreal. It also had a section for feminist publications and gender-neutral books for kids. Founded in October 1973 and first located on Crescent street, it was managed by a small team, which was then joined by a group of volunteers in the fall of 1975. These volunteers formed a collective of lesbians, heterosexual women and gay men which operated until 1982, at which point the bookstore became a private business. From 1974 to 1977, Androgyny shared its location with the political bookstore Alternatives, linked to publisher Black Rose Books. In June 1975, Androgyny bookstore moved to a more spacious location on Crescent. It later moved to Saint-Laurent Boulevard in 1982, and finally to Amherst street (now renamed Atateken) in 2001, until it closed in 2002. While Androgyny first sold English language publications, the bookstore collective recruited francophone members in 1976 and adopted the name “L’Androgyne” in 1978.

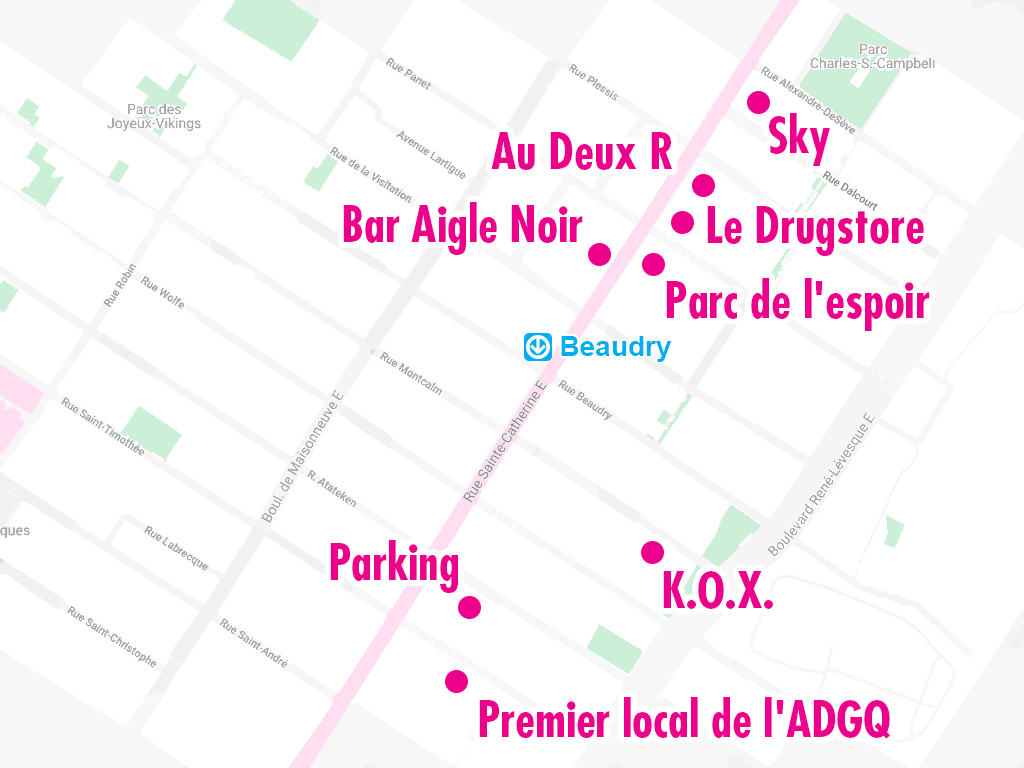

The Village

The New Village of the East, contrary to popular myth, did not move to the East directly due to police violence or because of the “Olympic cleanup.” The Village took off in 1983 – many years after these raids. Economic factors, such as the increasing rents in downtown Montreal and the low cost of commercial spaces in the East, encouraged a number of entrepreneurs to open new establishments in what is now the Village. In addition, the architecture of the buildings, which were used as theaters, cabarets and cinemas earlier in the 20th century, was favourable for those who wanted to open bars. In the beginning of the 1980s, multiple bars and gay establishments still existed in the West Village and in the Red Light District, as the bars in the new Village multiplied; In the 1990, most of the gay establishments of Montreal were situated in the new Village. Once home to multiple large multifunctional complexes, such as the Bourbon, the Village’s unique character is currently threatened by gentrification, with bars and large complexes being replaced with condos.

D.V.: I think, the Village back then, even in a period where we were getting more and more accepted, it was still like an oasis, where we felt safer as a part of the city. The Village was a place where you could like, hang out with your friends, and only really gay people would hang out there, so, if you were in the closet you weren’t too worried about that if you hadn’t told your family yet, like – ugh, the struggles! We felt that that was a pretty safe space.

M.B.P. : Même si je suis proche du village en plus … je me sens quand même comme un objet sexuel, plutôt qu’un humain, donc ça l’influence beaucoup mes craintes – ou pas mes craintes mais ça va beaucoup influencer ma perception de la réalité ou des réalités.

J’étais dans le village quand je pouvais sortir dans les bars. Je suis jamais allé.e quand j’étais mineur.e, mais j’ai jamais aimé mes expériences là-bas. C’était plein de blancs, soûls … qui vont me traiter de sexy boy ou de genre beau sauvage ou j’sais pas quoi pis j’suis juste comme … non. Ou me faire pogner les fesses, sans mon consentement… en tout cas – Exclure aussi mon amie fille parce que c’est une fille dans un bar gai. Voilà, fait que j’y allais pis j’suis pas allé.e longtemps.

A.P.: And I remember leaving all my suitcases and everything there, and then coming out, and going on the street, and then going on Sainte-Catherine, and walking, just walking, like it just felt like, the most amazing feeling in the world, it just felt like … [inhale] something I had never felt. […] And I remember, just walking and saying like, “One day I’m going to live here” like, “This is the place where I belong”

Adress : 1182, rue Montcalm

(1984-1996)

1182, Montcalm street (1984-1991)

Station C, 1450-1456, Sainte-Catherine East street (1992-1996)

Officially opened in February 1984, the K.O.X. is also among the first bars of the Village.

M.W.: So one night I’m at K.O.X. […] And I went pretty nuts one night and I started making out with a guy. And I guess we were getting a little bit too heavy. Maybe clothes were starting to come off but, I got tapped on the shoulder and I got asked to leave, and I’m like, “I wasn’t doing anything that outrageous!” and they were like, “this is a gay bar ma’am.” I’m like, “but I’m bisexual and so is he!” And we got kicked out because we looked like a straight couple, making out too much in a gay bar when we were both bisexual. Yeah, in 1992. Can you believe that? I got kicked out. I’m kind of proud of it now, like “I got kicked out of K.O.X.!” people are like “What?! I’ve been fisted in K.O.X. and I didn’t get kicked out.” [laugh] Anyway, yes I got kicked out – and the guy was a member, he had a membership.

Excerpt from Flâneries et souvenances, Bernard Mulaire

« Une nuit, au sortir du bar bien nommé K.O.X. […] je me suis retrouvé dans le terrain vague qui l’entourait. Précisons que le bar attirait autant des professeurs d’université, des gérants de banque et des hommes d’affaires que des pères de famille, des étudiants, et des voyous de toute sorte. Était-il quatre ou cinq heures du matin? et voilà qu’une voiture de police arrive et braque ses feux sur nous. Aucun cafard n’a aussi vite quitté les lieux. J’ai trébuché, me suis blessé au genou, me suis sans doute réfugié dans un sauna, que j’ai sans doute quitté au matin, en prenant le bus pour chez moi, tout écorché, parmi les travailleurs qui, tout frais douchés et peignés, se rendaient à leur boulot. » -- Bernard Mulaire in Flâneries et souvenances, p. 271

Adress : 1366, rue Sainte-Catherine Est

(1998-2013)

The Drugstore was a large multi-story complex, popular with the lesbian community. It also served as a meeting place for LGBT groups. The Drugstore's liquor licenses dated back to 1908 and bore the original name of the establishment it had replaced, La Taverne du Village de l'Est.

M.G. : Le vendredi soir aussi, le grand truc c’était d’aller au Drugstore. Le gros bar, sur quatre étages, avec plein de lesbiennes. Et en fait ce que j’aimais bien aussi c’est qu’il y avait une diversité de classes sociales que tu retrouves – que j’ai jamais jamais j’ai retrouvé nulle part ailleurs […] C’était agréable de rencontrer aussi des – pour moi en tout cas de savoir qu’il y avait des lesbiennes plus âgées, et qu’elles avaient encore le droit de sortir, qui sont pas du même milieu que moi et… c’est les seules fois où j’ai rencontré des gens qui sont pas dans le même milieu, qui pensent pas comme moi, qui n’écoutent pas les mêmes choses, qui lisent pas les mêmes choses, et pis que, quand on se rencontrait, on partageait nos histoires de lesbiennes pis ça allait pas trop – plus loin que ça parce que on avait ça en commun mais pas tant d’autres choses mais déjà ça je trouvais ça super en fait. Moi ça me rassurait beaucoup en fait, de pouvoir avoir cet échange-là. Et ça n’existe plus ça, ça n’existe plus. […] Je trouve ça dommage qu’il n’y ait plus cette mixité d’âges, c’est ce qui me manque, moi. C’est d’avoir l’impression que … quand t’es vieux t’es mort quoi, si t’es un vieux queer t’es mort, t’existes plus.

Adress : 1296, rue Atateken (auparavant Amherst)

(2000- 2011)

k-l. : Il y avait le Parking, le jeudi avec DJ Mini, qui pour moi était très important parce que le jeudi on savait qu’on allait rencontrer plus de lesbiennes, d’avoir des DJettes lesbiennes, ouvertement lesbiennes, c’était cool moi je trouvais. Parce que quand même, je pense que la communauté lesbienne est plus à risque. Quand même, avec … patriarcat, même avec les féministes parfois, d’être lesbienne c’est pas – même si on dit que oui on accepte, on est féministes, on aime toutes les femmes, moi je vois pas ça tellement encore. Il y a tellement de choses à travailler sur nos propres … notre éducation colonisée, tout est colonisé, tout ce qu’on lit, c’est toujours des références de femmes blanches, féministes blanches, c’est ça qui est prôné.

M.W.: So Parking had a second iteration – it wasn’t as good okay – they had moved location and then finally they got shut down for fucking condos. And ruined that spot. It was the best club. It had all those different spaces, nooks and crannies, clean bathrooms, and a giant terrace, like Sky. So even in the winter – they didn’t allow to smoke inside anymore – you would go up the stairs, and you would have like, little blankets on hooks. So even if you were wearing your skimpy disco outfit, you can pull in a blanket, and you go outside in the snow, in the rain, and have your cigarette and you had heaters, and little covered spaces. It was so much fun. I made out with so many people at that club, I can’t even tell you. […] They had some great DJ’s there […] it was so awesome.

M.W.: Straight guys would come to hear the DJs, ‘cause that’s how good the music was. Even if they were intimidated about being in the Village. That’s how good the club was.

Adress : 1264, rue Saint-Timothée

(used between 1977-1981)

Following the protests against the raids on the Truxx and the Mystique, the ADGQ continued its struggle to demand an addition to Quebec’s Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms that would protect gays and lesbians from discrimination. Bill 88 passed on the 15th of December of 1977; Thus, Quebec became the second government in the world to forbid discrimination based on sexual orientation. The location pictured above is the ADGQ’s first address, which it occupied from 1977 to 1981.

Adress : 1294, rue Panet #1310

(inaugurated en 1994)

Officially inaugurated by the City of Montreal in 1994 with a commemorative plaque for those who died of AIDS-related complications, the Parc de l’espoir is a protest space for HIV/AIDS organisations and gay groups since the 1990s. The parc continues to be a gathering and protest space: in 2016, following the PULSE shooting in the United States, Montrealers gathered in the parc for a vigil for the victims.

Adress : 1474, rue Sainte-Catherine Est

(1995- today)

M.W.: Back in the day, Sky was a cool club, did you know that? […] like, really really cool, it had three totally different bars. And I used to go to the underground one – the cave they used to call it. […] they used to play all really alternative music […] you know, like really alternative music, not on the radio, popular but not on the radio and it was awesome, and I think every single time I went down in that cave, I had at least three shots and ended up making out with some girl or a boy, like every time, every time. […] And then as things progressed in the 90s, Sky was doing all kinds of night. I remember at one point, and this is when I was really swinging out with the sisters as they say, they even had a Latina – now we would say Latinx – a Latino Thursday night.

Adress : 1315, rue Sainte-Catherine Est

(1992- today)

M.W.: I started getting very comfortable in the leather scene, ‘cause I realized, I’m a leather man. That’s my thing. Maybe it connects to my Indigenous roots? I don’t know. First time I put on some leather, it was oh this is me, you know? I wasn’t wearing an outfit, this is part of my identity.

M.W.: So I started going out with one of my friends who is a big leather bear. And I’m talking like, he takes his shirt off, he wears a harness, and chains, and shorts, when he goes out, like, for real for real. And I started feeling so comfortable in that environment that I started going to Stock, the Stud, and the Black Eagle. It became the places I hung out. […] But then they changed owners, and changed back, and one of the owners is very … anti-woman. It didn’t matter if I was queer, it didn’t matter if I was leather, it didn’t matter if I was kinky, he did not want any pussy sitting at his bar. It was awful. […] [He didn’t let me do a photoshoot in there (?)], and I really wanted to do a photoshoot there, because, if they haven’t changed it – have you been to the Eagle? […] A fun thing about the Eagle is that they have a great mural, a Tom of Finland mural.

A.P.: Now it makes me sad to go to the Village because there’s all these businesses are closing down, it’s not the same, it’s not the same feeling anymore because now there’s all these apps, there’s Grindr, there’s all of this. Before, we would go, to the bars because that’s where you would meet people […] And so Grindr, and all those apps completely changed all of that right. It kind of like, killed [laugh] you know, what the Village was and that sort of sense of community.

M.G. : je suis très attristée par le capitalisme rampant qui rentre dans tous les milieux LGBT, donc, tu vois, au début quand on faisait la fierté par exemple, et qu’on était dans la rue, il n’y avait pas de char, on était dans la rue nous-mêmes, en train de manifester. Aujourd’hui, toi en tant qu’individu, si tu vas à la Pride, moi j’y vais plus, j’ai arrêté ça. Mais, t’es sur le côté en train de regarder un défilé, c’est absurde. Et pis qui défile? Ce sont des corporations.

D.V.: But now, you know, people talk about it dying, what’s the use of a Village, everything’s online, there’s like Grindr for hookups, people don’t have to go to clubs anymore, I mean all this stuff is transforming the Village, but, you know, as much as people say that it’s dying, you know, just one cool bar opens up and everyone is there suddenly. So I don’t think it’s a matter of the Village it has to die, I think it’s a matter of the Village needs to keep evolving, and give people interesting spaces that have something interesting to offer.

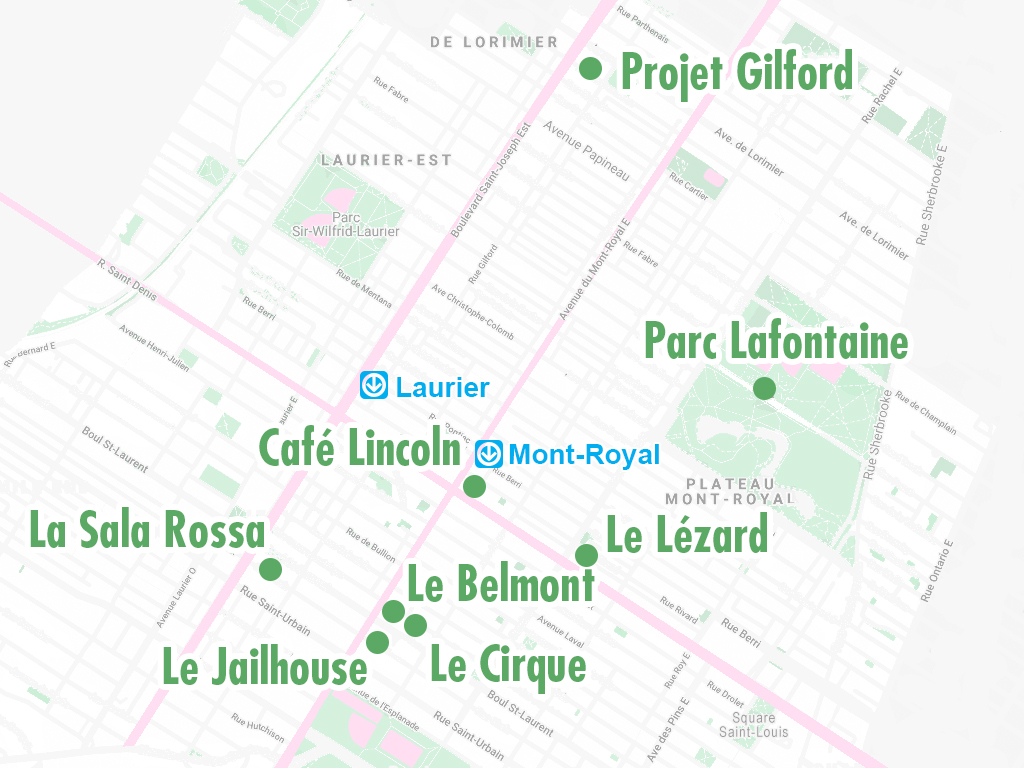

The Plateau

If the Village is gay, the Plateau Mont-Royal is, historically, a lesbian neighbourhood, even if it is so in a more informal manner than the Village. During the 1980s, or the “golden age” of lesbian visibility in urban space, the Plateau was home to many lesbian bars, cafés and community organisations. Though the amount of “mixed” establishments increased in Montreal, the number of exclusively lesbian bars fell significantly in the 1990s, while gay men kept establishments exclusive to men.

The gay and lesbian communities of Montreal followed different trajectories. Women being excluded from taverns until 1971, they could not have exclusive bars in the same way as men did. In mixed gay rights organisations, lesbians were often pushed aside. As such, lesbians – mostly middle-class – decided to create their own spaces, and settled in great numbers in the Plateau area. The first lesbian organisations, such as Montreal Gay Women (1973-1974) and Coop-Femmes (1977-1979), were situated in the Southeast limits of the Plateau.

M.G. : Ouais, à l’époque les bars de filles c’était vraiment aussi sur le Plateau. […] En fait, je pense que c’est entre Rachel et Sherbrooke qu’il y avait plusieurs bars. Je me souviens il y en a un qui s’appelait le Dietrich, il y en a un aussi s’appelait l’Exit, et ça s’était les bars où on allait prendre des bières et jouer au billiard. Donc j’ai appris à jouer au billard au Québec, tout le monde jouait au billard – en fait tout le monde – les lesbiennes [rire]. Et après il y avait d’autre bars où on allait pour danser. Donc le Sisters, dans le Village. Il y avait le Sisters, le Unity, on faisait souvent la tournée en fait.

M.W.: Earlier on in my queer explorations, I felt very excluded by the “gold star lesbians.” They didn’t believe in bisexuals. Which then people said it too, “I don’t believe in bisexuals, make up your mind,” I said I did make up my mind, I like both. I like pussy, I like dick. I like to give it, I like to get it. [laugh] And I’m a switch too, in the kinky world. I’m made this way, I’m so sure. But we didn’t have those terms back then.

M.W.: It’s funny, it was a lot easier for me later, after I came out as kinky, it was a lot easier to come out as kinky than to come out as bi, because … I just felt like that never suited my identity. I was pretty happy when Two-Spirit got rediscovered, or got put back on the table.

A.P.: It was nice in the Plateau because it’s super gay friendly as well so you always feel… I mean, pretty much I guess … a lot of different areas of Montreal feel safe and you feel sort of like, okay. But yeah, I’ve always loved the Plateau.

Adress : 4177, rue Saint-Denis

(1987-1994)

M.W.: It was very alternative but you didn’t have to be alternative to go there. You know there were some really gothy bars where if you didn’t have tons of makeup and the right clothing, they’re not gonna let you in. With this place, the Lézard, I could go in there in my full, black, fishnets, you know the whole thing, lots of makeup, and I could bring a preppy, totally preppy, white ass boy from Sherbrooke, who studies business at HEC, and he would feel comfortable there. And there would be someone with a Mohawk and black tape on her tits, and she felt comfortable there. And you’d see long-haired [rockers?], and you’d see punks, and you’d see students, and you’d see that everybody mixed, and there was always a lot of action on the floor.

Adress : 4479, rue Saint Denis

(1936-1985)

« On m’avait prévenu : « Dès que t’es entré, prends l’escalier à gauche et va direct à la galerie au 2ème sinon tu vas te faire achaler... » De la rue, l’escalier était déjà sombre, le bruit s’amplifiait très vite en grimpant et j’ai cherché la poignée de la porte dans une noirceur quasi complète. Et là l’explosion : des tables entassées archi-combles de types de tous les âges qui enterrent la musique de leurs cris et hurlements, jouent du coude et se bourrent les côtes en pouffant de rire comme des gamins. Mais je suis aussi accueilli par une drôle d'Élégante tout en bouclettes grises et vieilles dentelles, bijoux clinquants, bouche écarlate qui me demande d’autorité mon âge et « As-tu dit à ta mère que tu venais ici ?!? », ajoutant immédiatement à haute voix en me pointant du doigt pour l’assistance : « Un Nouveau ! » - gros rires, sifflets et trépignements - j’ai à peu près l’allure d’un jeune séminariste échappé du noviciat et tout le monde a bien vu que je n’étais pas du coin; à 24 ans, je n’en parais pas encore 17. Et la vieille madame, c’est ‘La Goulou‘, un vieux rigolo du quartier qui joue les travestis le samedi soir - nom d’artiste évidemment inspiré de La Goulue du Moulin Rouge, Paris, immortalisée dans les affiches de Toulouse-Lautrec. Je prends l’escalier à gauche tel que prescrit, la scènette d’entrée a en fait duré à peine trente secondes. Dans la galerie de l’étage, autre clientèle, gens discrets, plutôt sérieux, qui sourient aimablement au nouveau venu un rien secoué, dont un intellectuel et critique célèbre à l’époque qui ne craint rien de plus que d’être vu là, au Lincoln. Il y aura suite. J’apprendrai aussi plus tard la visite d’un client très singulier, amateur de spectacles amateurs, car il y avait le dimanche de ces spectacles où, par exemple, un garçonnet de 7 ou 9 ans chantait La Vie en Rose accompagné à l’orgue Hammond par un autre vieux monsieur, cette fois à perruque Elvis qui lui glissait parfois sur l’oreille, la maman du petit chanteur essuyant ses larmes juste à côté. Et ce client particulier, ravi de son incognito au Lincoln, c’était Leonard Bernstein, l’auteur de West Side Story, encore frais. Je reverrai La Goulou vingt ans plus tard au hasard de l’Aigle Noir, doux vieillard discret et timide qui entreprend de me causer - je ne l’ai évidemment pas reconnu, mais dix minutes plus tard, c’est chose faite. Je lui raconte tout ça, ma première sortie au Lincoln, Leonard Bernstein : grande émotion - plus personne ne le connaît, quelques larmes. Je trouverai peu après chez un bouquiniste une jolie reproduction - format réduit - de La Goulue de Toulouse-Lautrec. Je l’achète, l’encadre sobrement, lui donne au 5 à 7 de l’Aigle. Je resterai ébranlé par l’énorme reconnaissance de La Goulou, ses amis même viennent me remercier - il a gardé le petit cadre bien en évidence à la tête de son lit jusqu’à sa mort, l’année suivante. Je crois qu’il s’appelait Émile... » -- Pierre M.W.

Adress : 4848, boulevard Saint-Laurent

(built in 1932)

The Sala Rossa was built in 1932 by Montreal’s Jewish community as a center for cultural, recreational and political activities. The Centro Social Espanol now uses the building as a cultural center for Spanish-speaking people. The Sala Rossa is known for hosting events such as Kiss My Cabaret, the Meow mix, The Goods night, and balls. Meow Mix parties (1997-2012) were created by Miriam Genestier and her then girlfriend, Irene, for “bent girls and their buddies”.

k-l. : puis il y avait les soirées Meow Mix […] Donc ça c’était plus lesbien mais ce que j’aimais bien dans les soirées Meow Mix c’est que c’est des lesbiennes, et leurs copains ou copines. Enfin, c’était pas juste que des femmes. Ça j’aimais beaucoup parce qu’il y avait une crowd beaucoup plus artistique mais aussi des gens de Longueuil, et c’était leur sortie, ou de Laval. Donc il y avait un mélange d’âges, il y avait un mélange de styles… C’était très convivial et moi j’aimais beaucoup ces soirées-là. […] Donc Sala Rossa c’était le lieu où ça se passait. Ça c’était plus 2006… quand moi j’suis arrivé.e à plus ou moins deux mille […] 2010 je dirais, 2012.

(inaugurated in 1901)

Parc La Fontaine was known as a cruising spot for gay men, at least until the turn of the century, as was Parc du Mont-Royal. This park has also been a place of struggle: in 1979, a mixed demonstration for gay rights of about 200 people took place there. So did the first gay pride march of Montreal organised by John Banks in 1979 also, where about 200 people marched between Square Saint-Louis and Parc La Fontaine.

A.P.: Parc Lafontaine was another place that we would, you know, go and hang out, and visit … And sometimes we would go there and see the people cruising at night or whatever.

Adress : 30, avenue du Mont-Royal Ouest

(1992-2001)

The Jailhouse was one of the venues that hosted the Meow Mix parties (1997-2012).

M.G. : J’ai toujours adoré aller danser, et plus ça allait, moins il y avait d’espaces pour les filles et alors il y a un truc qui était hyper important pour moi à l’époque c’est les soirées Meow Mix. C’était des soirées organisées par Miriam Ginestier qui est directrice du studio 303, et qui organisait dans les années 90, jusqu’à maintenant en fait, des soirées une fois par mois pour les lesbiennes et leur buddies. Ça veut dire que moi je pouvais amener mes copains pédés. C’est des soirées où il y avait des cabarets puis après on dansait. Et ça c’était génial parce que c’était le seul endroit où les anglophones et les francophones étaient ensemble et dansaient ensemble. Et à l’époque c’était très compliqué parce que les années 90s, enfin 1995 c’était quand même le vote pour l’indépendance […] Tu ressentais vraiment les deux mondes complètement … qui ne se parlaient pas je trouvais. C’était des soirées organisées par des anglos, il y avait beaucoup de francophones et il y avait un vrai mélange. C’était super et ça a duré des années. Et ça se passait au Jailhouse, c’était un bar sur Mont-Royal, et par la suite dans les années 2000, ça a bougé à la Sala Rossa

Adress : 4483, boulevard Saint-Laurent

(Mec Plus Ultra : 2008-2012)

The Belmont became gay at least once a month. In 2008, the bi-monthly Mec Plus Ultra (MPU) parties were created at the initiative of Julien de Repentigny, François Guimond and Antoine Bédard.

M.W.: Someone came up with a queer night at the Belmont. So this became a thing now. They would go to a straight area of town after Parking closed and whatever. Or around the time it was transitioning. And they’d just talk to the owners and go, okay, we know that your Saturday night is heterosexual douchebags. But can we have Thursday? Or can we have one Saturday a month? […] Cause a lot of gay guys started living in the Plateau, they weren’t living in the Village. The play on words for nec plus ultra became Mecs Plus Ultra. They would just become some really really really fun nights. First you would go to the Meow Mix, and they you would leave the Meow Mix early to go finish the night, with the gay boys at the Belmont so that was really fun.

Adress : 4465, boulevard Saint-Laurent

(unknown dates)

Le Cirque was one of the venues that hosted the Meow Mix parties (1997-2012).

M.W.: They were crazy the old Meow Mixes, I mean crazy! I mean shirts off, and everyone making out in a hot sweaty mess with their tits out. It was amazing. People would go crazy, so much fun.

M.W.: You know in the beginning when people were trans or non-binary, and trying to pass, it was really hard for them in the beginning. That was one of the few places that would let them in. It’s not like now, someone is a butch for a minute, and they transition, okay, people were butch for ten years before they even considered taking hormones or doing any kind of transitioning. It was a very strict dichotomy of femme and butch, which again I had a problem with.

Adress : 2025, rue Gilford

(1984-1993)

L’école Gilford was the main site of artistic and political activity for the French-speaking lesbian community in Montreal. The community and arts center was run as a cooperative by Arts et Gestes des femmes de Montréal.

« Gilford était constamment achalandé. Des artistes s’y rendaient quotidiennement pout s’exercer, travailler sur leurs productions ou donner des ateliers. Alors que les enseignantes et étudiantes de l’École des Arts martiaux des femmes de Montréal pratiquaient le karaté et le tai-chi dans le gymnase les soirs de semaine, des ébénistes oeuvraient à temps plein au sous-sol. Simultanément, deux peintres habitaient leur atelier tandis que des musiciennes partageaient une salle de répétition avec la Chorale lesbienne. Un plus petit local abritait les Archives lesbiennes Traces pendant qu’une imprimeure mettait sa presse au service de publications lesbiennes. D’autres groupes, par contre, ont utilisé la bâtisse de façon plus ponctuelle; par exemple, Alcooliques Anonymes y a tenu pour un temps des réunions dominicales pour femmes. Lorsqu’un événement était en préparation – ce qui était souvent le cas –, l’édifice entier bourdonnait. Ajoutons que l’école était gérée selon un mode coopératif par ce qui s’appelait officiellement Arts et Gestes des Femmes de Montréal, une collective qui réunissait des représentantes de chacun des groupes, lesquelles prenaient ensemble les décisions concernant le fonctionnement et l’orientation de Gilford. » -- Suzanne Boisvert et Danielle Boutet dans Sortir de l’ombre, page 315.

k-l. : C’était safe. Au moins je savais que j’allais pas me faire ennuyer par un dude ou une pitoune qui me disait de pas rentrer dans les toilettes ou qui m’interdisait, etc., mais il y avait un autre pendant, c’était le racisme aussi. […] Ou bien il y avait le fétichisme des Afro-descendant.e.s souvent, c’était « oh la Black! Je t’aime parce que t’es Black » ou « Je t’aime parce que t’es Asiatique, » ça aussi c’était un peu chiant, parce que ça fait partie de la game, après c’est à toi de te défendre et ne pas accepter ou remettre la personne en place. C’est pas parce que t’es gai, Occidentalement passing white que tu ne fais pas des faux pas ou tu fais pas des énormités – pas des insultes raciales mais comme, un peu condescendantes. Enfin, le colonialisme existe partout et ça c’était quelque chose que je devais gérer en plus.

The Red Light District and the Main

The Red Light District is a rectangle roughly defined by Saint-Laurent boulevard at the West extremity, Sherbrooke at the North, René-Levesque (previously Dorchester) at the South, and Saint-Denis street at the East. The Main is the nickname of the western extremity of the rectangle – the lower Saint-Laurent boulevard.

In the years following World War II, this neighbourhood already had a bad reputation due to its association with organised crime, sex work, and visibly non-heterosexual people. For lesbians in the 1950-60s, the Red Light bars and cabarets were their main meeting places. Even though lesbians, gays and crossdressers socialized in these bars and cabarets, many of them had a mixed clientele, meaning that heterosexuals frequented them too. That being said, middle and upper-class, as well as anglophone gays and lesbians tended to avoid the Red Light, due to its negative associations. Despite all, for those who frequented the establishments of the Main and the Red Light, these spaces were cherished and important, because they allowed for a freedom that the rest of society did not grant those who lived on the margins.

P.M.W. : Il y avait évidemment l’époque des bars, ce qu’on appelait les trous, les trous de la Main, de la rue Saint-Laurent. Mais là, on allait pas parce que c’était carrément le quartier euh … le quartier des putes et des vraies tapettes, c’est-à-dire les vieux pédés, les vielles tapettes des années 50, hein, très très caricaturales, auxquelles on voulait surtout pas être associés. C’était, on était assez, comment dire, résistants de ce côté-là hein. Ben évidemment. L’image à l’époque de l’homosexualité c’était évidemment tout ce qui était visible c’est-à-dire –ridiculisé, féminité, travestis, etc.

Adress : 162, rue Sainte-Catherine Est

(late 1920s- 1990s)

Established in the late 1920s, the Monarch Café, or the “Zoo” as it was also known, is one of the first established gay venues on the east side of the city, as well as one of the only permanent establishments from the 1945-1960s that was exclusively for gay men.

«We used to go very often from there [Montreal Swimming Club] at the Monarch or the Zoo. We were always treated like royalty. They had contests that the guy used to play the piano and if you could guess the name of the song you got a free beer and that sort of stuff.» Armand Monroe dans A Sense of Belonging (Higgins 1997, 278)

«The customers were of an oIder age group. The Monarch had a dance floor where a sign I observed in the mid-1970s forbade slow dances. Pierre explained: Oui, oui, oui, ils voulaient pas avoir de troubles avec la police. C'était une mesure de protection pour l'escouade de la moralité. Comme aujourd'hui, avec les affiches sur les drogues. » (Higgins 1997, 283)

Adress : 1278, rue Saint-André

(1956-1988)

The mixed clientele of Les Ponts de Paris was divided into three sections: lesbians were seated to the left of the stage, heterosexuals and gays were on the right, and those who wanted to pay for sexual services sat at the bar. In the 1950s, Les Ponts de Paris became well known to the public as a meeting place for lesbians. This allowed more lesbians to know about the place, sometimes through unsuspecting family members. However, the increased popularity also meant that they were exposed to the voyeuristic eyes of other customers. Narrators in Chamberland's research project (Remembering Lesbian Bars, 1993) who were patrons of Les Ponts de Paris described it as a warm place where they could have fun, attended lesbian weddings, and met friends.

Adress : 302, rue Ontario

(1980-2012)

La Paryse was one of the restaurants and cafes regurlarly frequented by lesbians. Like many other places whose customer base is not explicitly LGBTQ2S+, having many LGBTQ2S+ employees draws in non-heterosexual people and contributes to a feeling of safety.

M.G. : Et puis on allait manger aussi à la Paryse à l’époque parce que il y a plusieurs ami.e.s qui travaillaient là, donc on était sûr de trouver des gens qu’on connaissait, la bouffe était bonne puis elle était abordable, pour les gens comme moi qui avaient pas trop d’argent.

Adress : 1230, boulevard Saint-Laurent

(1976-today)

Opened during in the mid-1970s, the café Cléopâtre is the last of the old Red Light District establishments that remains open. While the first floor offers striptease shows aimed at heterosexual men, the second floor has shows featuring drag queens and trans people who were marginalized even within the gay community.

P.M.W.: [Parlant des années 70] le Cléopâtre était déjà là, et c’était le vrai Cléopâtre avec, les danseuses, les travestis, les gais, les p’tits dealers et tout le truc.

M.W.: Now, if you were charging money at the door, and you wanted to have alcohol, you couldn’t have alcohol in the same room as people were getting naked, did you know that? Isn’t that crazy? Yeah, you know the only place in Montreal that has a licence to perform on stage, sell alcohol and do a full Monty, a full frontal, and it’s the fucking café Cléopâtre.

Adress : 94, rue Sainte-Catherine Est

(1954-1974)

Opened in 1954, the Casa Loma among the many Montreal cabarets operating during the 1950s and 1960s. Though the patrons were not exclusively homosexual, many gays and lesbians frequented it. This cabaret, like many others, gave drag shows, which were rather popular at the time. Well-known artists performed there as well, such as Ginette Reno, Alys Robi and les Jérolas. The Casa Loma closed in 1971 due to multiple pressures: TV providing entertainment directly at home, the opening of the Place des Arts, as well as a triple murder linked with organized crime at the Casa Loma.

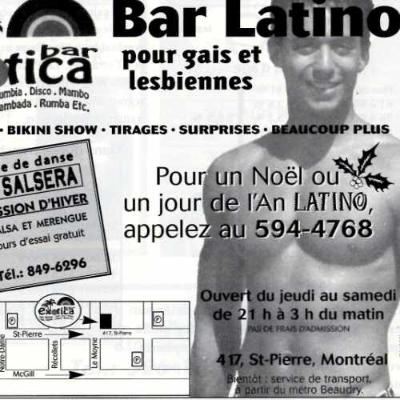

Adress : 417, rue Saint-Pierre

(unknown dates)

Situated away from the main gay poles of the city, Exotica was a Latino bar in the Old Montreal.

A.P.: At the time, there was a gay Latino bar and it was called Exotica. And that one wasn’t in the Village, it was in the Old Montreal […]

A.P.: It was funny, I mean it was – because, first it was outside of the Village, it was in the Old Montreal, so you know, you would get that feeling of going into the old buildings right, and everything and then you would go, and it was kinda in the basement of the place, you would have to go down a little bit , and it had, these, crazy red velvet curtains, you know like – Yes [laughter] yes oh my God [still laughing] like a sex … um parlor or something, or a brothel kind of thing, and it had like these chandeliers, and the red velvet curtains, and the Latino music playing, and it was also kinda funny and kinda sketchy now that I think back, but it was all these old, white, men, who were like all standing from the bar, behind the bar like looking at all of the young Latinos dancing.

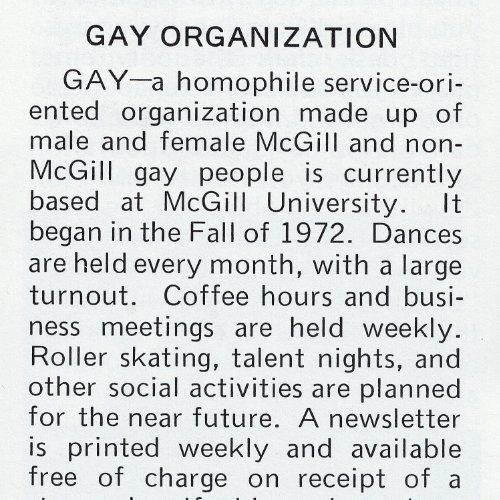

University and College groups

LGBTQ2S+ associations in universities and cégeps played and continue to play an important role in the life of LGBTQ2S+ youth. For example, groups like Gay McGill, formed in 1972, responded to needs such as education on gay topics, psychological support, and simply organizing social events. Notably, Gay McGill’s dances could include hundreds of participants. The cégep du Vieux-Montréal and the cégep Maisonneuve also organized similar events. Student LGBTQ2S+ groups continue to provide community and provide access to information on sexual and gender identity.

Adress : College Dawson, 3040, rue Sherbrooke Ouest

(1985-today)

D.V.: I felt completely safe at Dawson. Dawson’s like, a very urban CEGEP, it’s the largest CEGEP in Quebec, it is… like … it feels like you’re in New York City. It feels like everyone’s busy, too busy to be involved in you, you can be anonymous, there’s so many people, the halls are crowded, everyone is different, it was – you’re like, anonymous in a crowd.[…] In particular there was a kind of club space, a space designated for clubs on campus, and there were actually several rooms, but there was one in particular, 2C.12. It was on the second floor, it was in C corridor, and it was room number 12. And it was like a real refuge for a lot of queer kids, because that was the club space for Etcetera, which was the queer, LGBTQ+ club on campus. So, it was also shared with the feminist group on campus, which was called Young Amazons, and GAIA, which was the environmentalist group. And, it was like, a very liberally-minded, very progressively-minded, almost militantly-so … this space where it was like radical inclusion. While we were anonymous, and sort of just like, no one heard about us in the hallways, that was a place where we actually felt accepted.

D.V.: 2C.12 only exists in photos, ‘cause I think, I went back like, years later and they reconfigured that whole floor. And they, like, Etcetera and that space is not a club space anymore, and it’s like, completely different. So 2C.12 only exists in our memories now

D.V.: In the end it only matters the chemistry of the people. The space was like, just, like a canvas, for what we felt. And that is really more what I remember, it’s like, the way we felt like a community then. We like, loved each other so much.

Montreal, in decline?

It is becoming clear that gentrification is intensifying in the Village, just like in other Montreal neighbourhoods. Village businesses report that they are making less and less profits as time goes by. Is it a sign that LGBTQ2S+ are less necessary to meet new people or to feel safe? Or is it, on the contrary, a sign of further marginalization, as municipal policies let gentrification go unchecked? Whatever the answer may be, the lack of spaces and dedicated to LGBTQ2S+ people and the closing of many places dear to community members does not go unnoticed.

M.G. : les femmes ont de moins en moins d’argent. Clairement. Donc, elles sortent moins, elles dépensent moins. Les bars, pour les femmes, peuvent pas exister longtemps, ça c’est très clair. […] Il y a plus rien à Montréal, il y a plus rien. Il y a que des endroits pour les gais, et… pour qui? Et encore, tu vois, j’ai des amis gais qui veulent plus sortir parce que les lieux sont … un peu glauques. […] C’est toujours éphémère. En fait, les endroits où je vais il se passe des choses c’est les festivals. Musique, films, ou autre chose, et je suis sûre de retrouver une communauté de gens.

M.B.P. : [parlant de centres communautaires LGBTQ2S+] je sais qu’il y avait Arc-en-ciel d’Afrique, mais ça l’a fermé il y a quelques années, ça l’a fermé quand je commençais à m’ouvrir. Donc, honnêtement non, à Montréal je connais pas mais, j’sais pas, ça a pas l’air … Il y a rien spécifiquement pour les personnes noires, donc – peut-être plus maintenant, donc, non.

New directions

Despite the decline of the Village and of lesbian bars, there are still queer and trans-friendly spaces around Jean-Talon Metro, and neighbourhoods such as Rosemont and Little Italy. LGBTQ2S+ people can also feel comfortable in places that are not explicitly queer or trans. After all, our identities are complex. Indeed, we are many communities, not a single one. Our multiple identities, be they gendered, racial, sexual, ethnic, linguistic, etc., make every single LGBTQ2S person’s experiences unique. Many of the narrators said that they would like to see more politicized LGBTQ2S+ communities that would collaborate closely with social justice struggles, such as racial equality or feminist movements.

M.G.: Pis là en ce moment là où j’habite c’est très très très très queer [rire] […] J’habite à côté du Pickup, j’sais pas si tu connais, c’est un endroit qui a été ouvert par la chanteuse – pas la chanteuse mais Bernie des Lesbians on Ecstasy notamment, c’était un groupe de lesbiennes dans les années 2000, et c’est quelqu’un qui a ouvert plusieurs endroits, ils ont ouvert un restaurant, ils ont ouvert un bar, et ils ont employé beaucoup de personnes de la communauté, donc ces lieux-là font que ça amène d’autres gens, donc les gens viennent habiter dans les quartiers puis c’est très très très très queer.

k-l. : Je suis né.e intersexe. Donc ça c’est aussi le I dans le LGBTIQ, […] c’est vraiment la dernière lettre. Même dans le défilé gai à Montréal, c’était il y a deux ans seulement, que ça a eu le premier – on a eu notre première petite banner là, on était 3-4. [rire] Mais bon, on était là quoi. Donc ça c’est aussi important c’est que moi je me sens ni fille ni garçon ou pas assez fille pas assez garçon; trop garçon ou trop fille. Ça ça dépend comment on le voit mais … c’est pour ça que je me sens plus agenré.e.

M.B.P. : T’as le sentiment d’objectification et tout qui traverse ma pensée. Je me sens pas jugé.e […] Pis c’est aussi que, il y a pas personne, pas personne qui me ressemble tant, donc c’est aussi ça qui manque dans qui je vais croiser par exemple. Pis surtout peut-être parce que, là je parle vraiment dans la communauté queer, par exemple dans le Village, des trucs comme ça, le Plateau, Rosemont, mais comme, il y a d’autres queers dans les quartiers racialisés mais … c’est un peu plus difficile [rire]. […] Les milieux politiques, sociaux, culturels, des fois, que je me sentais super bien, pis que comme, c’est venu un peu combler ce besoin-là. Aussi juste d’être dans une place, que tu te sentais accepté.e, les jugements étaient le moindre de tes soucis, pis ça, ça l’a vraiment passé par – j’ai fait partie, ben, co-créé.e avec d’autres gens, le collectif anti-raciste/décolonial à Québec Solidaire, avec des gens que je connaissais déjà pour la plupart. Là je viens de quitter parce que je veux me concentrer sur mes études et autres initiatives, mais, c’est vraiment des gens pis un espace qui m’a fait fleurir.

k-l. : Moi je vais dire que je me sens plus en sécurité en tant que lesbienne, ou lesbian-passing ou queer en tout cas qu’Asiatique, surtout au moment de la pandémie. Ça m’a un peu dégouté.e en fait, le fait d’être à Montréal pendant la pandémie. Ça m’a vraiment fait [son de nausée]. À un moment je me disais, est-ce que je me casse? Parce que j’en ai marre de pas pouvoir – de marcher comme un rat, d’avoir peur que quelqu’un me tape dessus quoi, ou m’insulte, ou me dise de retourner dans mon pays – ce qui est vrai, j’suis pas d’ici, mais eux aussi ne sont pas d’ici parce ce sont des enfants de settler […] je comprends qu’il y a aussi le stress de la pandémie mais c’est pas pour ça que tu dois cracher ton venin sur quelqu’un d’autre.

M.G. : Beaucoup de groupes – ben surtout des gais blancs, hein – oublient en fait les problèmes sociaux, et d’argent, et de … bah toutes ces questions! Que les mouvements LGBT mettaient en avant et que tout d’un coup ça disparaissait, donc, là je retrouve plus ce – Ben avec tout ce qui s’est passé, Me Too, Black Lives Matter, il y a beaucoup beaucoup – les gens comprennent que l’intersectionnalité c’est ultra important et qu’il faut pas l’abandonner … Donc c’est vers ces milieux là que je me tourne quoi.

M.W.: I discovered that Montreal has a very fun, naughty side, but it definitely suffers from what I like to call the Catholic hangover […] people would be like sitting on a terrace, and then be talking trash, talking sex, talking whatever, but then they’d be like “oh! [mocking judgement]” and you could just hear people either shaming someone, or blaming someone, that is Catholic and Protestant, and very North American and very, like either French or English, it’s so prevalent.

Conclusion

The neighbourhoods explored in the exhibit are far from the only places where LGBTQ2S+ people gather. There are as many LGBTQ2S+ spaces as there are people who identify as such. We make spaces queer and create queer spaces simply by existing.

This map cannot hope to capture all the experiences of LGBTQ2S+ people or all the issues we are affected by. Nevertheless, the interviews of only seven narrators already demonstrate how diverse our communities are. It is by telling our stories that we can understand where we come from, and it is by listening that we can decide our future directions.

A.P.: And I think that’s what Montreal is, like I mean it’s … of course there’s a lot of racism, there’s a lot of [pause] shit and you know whatever but! I decided, that this was going to be my safe place, even if it’s all in my head, but I decided that this was where I belong, and this is where I felt I belong.

D.V.: if it was your space, it would be a queer space

If you wish to speak about your own experiences, do not hesitate to leave a comment (the comment section is moderated).

If you wish to donate archival materials to the Archives gaies du Québec, please contact : info@agq.qc.ca

The full interviews used in the exhibit are available for consultation at the AGQ. Subscribe to our newsletter by contacting info@agq.qc.ca to know when the Archives will be open to the public again.

Acknowledgements

Words from the original curator of the exhibition: This exhibit would not have been possible without the collaboration of the seven narrators who generously shared their stories and their comments throughout my research.

A sincere thank you to Pierre, Armando, Derek, Ménélik, Mathilde, kimura and Michelle, not only for contributing as interview partners, but also for their advice, help in recruitment, and multiple photos in the exhibit, which make the exhibit come alive.

Thank you to the volunteers and employees at the Archives gaies du Québec who helped me to find photos and gave thorough feedback on the exhibit as I was putting it together. Thank you especially to Fabien Galipeau, archivist at the Archives gaies du Québec, for the help in locating archival materials, addresses, and for writing the texts for Androgyny Bookstore, the PJ’s, and the Casa Loma. I also thank Jonathan Proulx Guimond for designing the maps.

And finally, thank you to Mitacs and Summer Jobs Canada for financing the project.

We have sadly learned that Michelle Wouters passed away on October 28, 2022. Michelle was a 2-spirit survivor of the 60s scoop, and an educator in the Montreal community. We want to thank her once more for the infectious energy her stories brought to The Walls Have Ears. Her full interview is preserved at the Archives gaies du Québec and will always remain available. Rest in peace.

Additional thanks for the pedestrian version:

Thank you to the AGQ team of the summer 2021: Fabien Galipeau, Marion Daigle, Jonathan Proulx Guimond, et Simone Beaudry Pilotte.

Warm thanks to V. Samoylenko for the help throughout the process of adapting the exhibit.

Thank you for the financial support of: Emploi-Québec, Emploi d’été Canada, Québécor, the donors of the Archives gaies du Québec.

Thank you for the collaboration of: Archives Lesbiennes du Québec, Michelle Ronback, André Querry, André C. Passiour, Ross Higgins, the team of Village Montréal, and Fierté Montréal's team.

Works Consulted

Allan, JamesSky’s the Limit: The Operations, Renovations and Implications of a Montréal Gay Bar.Master's thesis. McGill University. 1997.

Archives Gaies du Québec. L’Archigai No. 21. November 2011.

Boulevard Saint-Laurent. «La Sala Rossa: À propos.» Consulted on June 24, 2021.

Chamberland, Line MA. «Remembering Lesbian Bars: Montreal, 1955-1975.» Journal of Homosexuality, Volume 25, Number 3. 1993. pp. 231-270.

Crawford, Jason B., and Karen Herland. “Sex Garage: Unspooling Narratives, Rethinking Collectivities.” Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes, Volume 48, Number 1. Winter 2014. pp. 106-131

Demczuk, Irène, and Frank W. Remiggi, éds.. Sortir de l’ombre: histoires des communautés lesbienne et gaie de Montréal. Montréal: VLB Éditeur. 1998

De Montigny, Julia. « Negotiating Everyday Spaces, Making Places: Queer & Trans* Youth in Montréal.” Master’s thesis. Concordia University. 2013.

Guindon, Jocelyn M. « La contestation des espaces gais au centre-ville de Montréal depuis 1950 ». PhD thesis. McGill. 2001.

Higgins, Ross. «A Sense of Belonging: Pre-liberation Space, Symbolics, and Leadership in Gay Montreal.» PhD thesis. McGill University. 1997.

Lafontaine, Yves. « Le Parc de l’Espoir. » Fugues. 26 July 2012. Consulted on 10 October 2020

-----. «Le Drugstore: Chronique d’une fermeture annoncée.» Fugues.

October 18, 2013. Consulted on June 24, 2021.Lecavalier, Philippe. «Le Village gai de Montréal: Un territoire d’appartenance en voie de disparition?» Master's thesis. Université du Québec à Montréal. 2018.

Podmore, Julie A.. “Gone ‘underground’? Lesbian visibility and the consolidation of queer space in Montréal.” Social & Cultural Geography, 7:4 (2006), 595-625. DOI: 10.1080/14649360600825737

-----. “Lesbians in the Crowd: Gender, sexuality and visibility along Montréal's Boul. St-Laurent.” Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 8:4 (2001): 333-355. DOI: 10.1080/09663690120111591

Radio-Canada Info. « Cabaret Casa Loma. » Youtube. 20 December 2016. Consulted 10 October 2020.

Fonds consulted :

Archives gaies du Québec. AGQ-F0187, Fonds Association des bonnes gens sourds (ABGS)

------, AGQ F-0017, Fonds Association pour les droits des gai(e)s du Québec (ADGQ)

------, AGQ-F0127/I-026 (photos B). Fonds John Banks.

-------, AGQ-F0141. Fonds Comité du Berdache 20 ans plus tard

![Interior of the P.J.’s. Photo credit: Unknown photographer. Date: [1970-1980?]. AGQ-F0050 Fonds Armand Monroe. Collection of the Archives gaies du Québec.](http://agq.qc.ca/documents/Lesmursontdesoreilles/Photos/P5-2m.jpg)

![Façade of the ADGQ’s first location. Photo credit: Stuart Russell. Year: [1977-1981]. AGQ-F0017 Fonds Association pour les droits des gai(e)s du Québec (ADGQ). Collection of the Archives gaies du Québec.](http://agq.qc.ca/documents/Lesmursontdesoreilles/Photos/P11-1m.jpg)

![The Parc de l’espoir, some time between fall 1993 and winter 1994. Red ribbons, symbolizing HIV/AIDS, are tied to the trees. Photo credit: René LeBoeuf. Year: [1993-1994] AGQ-F0107/ F202 Fonds Michael Hendricks/René LeBoeuf. Collection of the Archives gaies du Québec.](http://agq.qc.ca/documents/Lesmursontdesoreilles/Photos/P12-2m.jpg)

![Pride March. The crowd is still and observes a minute of silence for the victims of HIV/aids.] August 1996. Picture Credit : Michel Bazinet. Collection des Archives gaies du Québec.](http://agq.qc.ca/documents/Lesmursontdesoreilles/Photos/ND-1m.jpg)