During the summer of 2019, the Quebec Gay Archives renewed and actualised their previous exhibition titled “Stories of our Lives”. “Stories of Quebec LGBTQ2S+ Communities” includes the same content while integrating lived realities that hadn’t been taken into account previously, such as the experiences of trans folks. The exhibition aims to give a quick historical overview of Quebec’s sexual diversity. These new panels were displayed during Montreal Pride at the Cinéma du Parc between August 1st and September 22nd, 2019. We invite you to take a first, or second, look at our exhibition.

Click on each panel to see the detailed content

00

00 HISTOIRES DES COMMUNAUTÉS LGBTQ2S+

AN EXHIBITION BY THE QUEBEC GAY ARCHIVES

This exhibition explores, in eight panels, historical events in Québec from the 17th century to today. Those events demonstrate the evolution of homosexuality and lesbianism through the years, and the way in which society perceived sexual diversity in the past. It also explores contemporary issues in sexual and gender diversity. The first six panels of STORIES OF LGBTQ2S+ COMMUNITIES are based on the 17 panels that composed the Stories of our Lives exhibition, also available at agq.qc.ca. The last two panels were added to include a perspective on current LGBTQ2S+ realities. This exhibition was made possible thanks to Fierté Montréal. It will be displayed at the Cinéma du Parc from August 1st to September 22nd, 2019.

QUEBEC GAY ARCHIVES

Our mission

The Quebec Gay Archives have a mandate to acquire, conserve, and promote all documentation which relates to the history of LGBTQ+ organizations and individuals in Quebec.

To promote the diversity and the inclusion of LGBTQ+ people.

To continuously update its collection on all aspects of gender and sexuality.

To promote research on sexual minorities and gender and recognition of the contribution of the same to the history of Quebec.

An essential role

Through the conservation of archival fonds and collections, by the organization of public events and by welcoming researchers and visitors to its reading room, the Quebec Gay Archives perform an essential role as guardian and promoter of LGBTQ+ history, both locally and abroad.

One team

The AGQ’s work is entirely assumed by a dozen volunteer members who are involved in different ways in the sound administration of the organisation and of its collections.

We are always looking for new people interested in working with us to maintain and develop the Archives.

Our collections

Our collections include prints (books, periodicals, posters, flyers and press releases), manuscripts (personal or institutional), pictures, videos, movies, and a wide range of varied works of art, including multiple paintings.

We hold approximately 1 000 periodicals, 2 000 books, 1 000 brochures and reprints, 2 000 poster, 50 000 pictures, 1 200 audiovisual documents, approximately twenty boxes of buttons, banners, t-shirts and other items, over 3 linear meters of press releases and 1200 files on groups, individuals, or themes, including 350 files on HIV/AIDS.

Our History

The Quebec Gay Archives were founded in Montreal in 1983, during a time where the booming gay community was facing a wave of police repression, and at the beginning of the HIV/AIDS crisis.

In 1985, the AGQ officially became an NGO, and in 1990, a registered charity organisation.

Funding

The Archives are funded by donations and specific bequests from individuals and corporations, as well as fundraising events. We also receive occasional government funding for specific projects.

Hence the importance of your involvement and implication in the history of LGBTQ2S+ communities in Quebec, Canada, and the world.

THANK YOU TO

This exhibition is a Quebec Gay Archives production presented as part of the Pride Montreal celebrations.

COORDINATOR Pierre Pilotte

WRITERS Fabien Galipeau, Louis Godbout, Laurent Lafontant, Shawn McCutcheon, Pierre-Henri Minot.

CONFERENCE SPEAKER Louis Godbout

GRAPHIC DESIGNER Folio et Garetti

DOCUMENTARY LOAN Guilda elle est bien dans ma peau : Phare-Est Média

In partnership with: FUGUES Magazine and the Cinéma du Parc

This exhibition was made financially possible thanks to: André Chénard, Fonds Diversité sexuelle-Laurent McCutcheon, Claude Gosselin, Pierre Landry, Charles Lapointe, Gilles Legault, Pierre Pilotte, Québecor, Succession Frank W. Remiggi, the Quebec Gay Archives donors and FIERTÉ MONTRÉAL.

01

01 Four cheeky buggers in New France

Montreal was founded by Catholic devotees rooted in a movement of religious fervor that swept over France in the 17th century. In 1648, barely six years after Ville-Marie was founded, a young drummer from the regiment was accused of the “worst of crimes”. The Jesuits who recounted his case intervened on his behalf with the Sulpicians, seigneurs of Montreal. His sentence was to be sent to the galleys, but was commuted on the condition of becoming New France’s first executioner.

The drummer’s partner is not identified, but it could well be an Indigenous person since the French explorers Charlevoix, Marquette, the baron of Lahontan, and many others, recounted that certain indigenous nations practiced sodomy and counted among them men who “don’t have any shame in adorning women’s clothing, & to subject themselves to the occupations particular to their Sex, from which resulted a corruption that cannot be put into words.”

In his directives to the colony confessors, the ireful Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier specified that only him could absolve “those who commit the detestable sins of Sodomy & Bestiality.” Fortunately, this inflexible and abhorred bishop was in Paris when, in 1691, two soldiers and a lieutenant of the Compagnie du détachement de la Marine (a detachment of the Company of the Navy) posted in Montreal were accused of the crime of sodomy. Interrogations were undertaken, but the lieutenant Nicolas Daussy de Saint-Michel obstinately refused to answer any questions. Daussy did not recognize the authority of the bailiff and demanded to be judged by the Sovereign Council, even though the two soldiers, Forgeron, known as La Rose, and Filion, known as Dubois, had already confessed. The Sovereign Council agreed and ordered that all interrogations be redone. From the deliberations of the Council, we may conclude that the crime had probably taken place in public, possibly in one of the numerous taverns of the city, since no less than eight witnesses are quoted. La Rose was sentenced to prison for two years and Dubois for three, while Daussy de Saint-Michel, held to be the instigator of the infamous crimes, was banished from the colony and ordered to pay two hundred livres to the poor as well as all the court costs. On the day of the trial, November 12th 1691, the intendant Bochart de Champigny summed up the ordeal in a missive to the Ministre de la marine (Minister of the Navy) with the following sentence: “The Sr St Michel, lieutenant accused of many dirty deeds commited with soldiers, was judged today by the Conseil Souverain and condemned to perpetual banishment from this country; he is returning to France by one of our ships." Considering that the prescribed punishment was burning at the stake, these sentences must be seen as relatively lenient.

Here is what we know happened to our four cheeky buggers: the drummer of the Maisonneuve regiment did not hold his office of executioner for very long, because as of 1653, the colony no longer had an executioner. Did he die of scurvy or another disease that was decimating the inhabitants of New France? Or did he escape from this infamous profession by running away to become a fur trader? As for Forgeron, known as La Rose, we know only that he was found in the hospital in a very poor state shortly after the trial. As for Filion, known as Dubois, he married three times and fathered seventeen children before his death in 1711. Obviously, he had multifarious interests. If your ancestors are from Quebec, there is a good chance he may be your ancestor. Finally, Daussy de Saint-Michel, back in France, had to pursue his military career. Let's bet that as a brave lieutenant, his banishment did not prevent him from taking up the charge with other soldiers.

In his directives to the colony confessors, the ireful Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier specified that only him could absolve “those who commit the detestable sins of Sodomy & Bestiality.” Fortunately, this inflexible and abhorred bishop was in Paris when, in 1691, two soldiers and a lieutenant of the Compagnie du détachement de la Marine (a detachment of the Company of the Navy) posted in Montreal were accused of the crime of sodomy. Interrogations were undertaken, but the lieutenant Nicolas Daussy de Saint-Michel obstinately refused to answer any questions. Daussy did not recognize the authority of the bailiff and demanded to be judged by the Sovereign Council, even though the two soldiers, Forgeron, known as La Rose, and Filion, known as Dubois, had already confessed. The Sovereign Council agreed and ordered that all interrogations be redone. From the deliberations of the Council, we may conclude that the crime had probably taken place in public, possibly in one of the numerous taverns of the city, since no less than eight witnesses are quoted. La Rose was sentenced to prison for two years and Dubois for three, while Daussy de Saint-Michel, held to be the instigator of the infamous crimes, was banished from the colony and ordered to pay two hundred livres to the poor as well as all the court costs. On the day of the trial, November 12th 1691, the intendant Bochart de Champigny summed up the ordeal in a missive to the Ministre de la marine (Minister of the Navy) with the following sentence: “The Sr St Michel, lieutenant accused of many dirty deeds commited with soldiers, was judged today by the Conseil Souverain and condemned to perpetual banishment from this country; he is returning to France by one of our ships." Considering that the prescribed punishment was burning at the stake, these sentences must be seen as relatively lenient.

Here is what we know happened to our four cheeky buggers: the drummer of the Maisonneuve regiment did not hold his office of executioner for very long, because as of 1653, the colony no longer had an executioner. Did he die of scurvy or another disease that was decimating the inhabitants of New France? Or did he escape from this infamous profession by running away to become a fur trader? As for Forgeron, known as La Rose, we know only that he was found in the hospital in a very poor state shortly after the trial. As for Filion, known as Dubois, he married three times and fathered seventeen children before his death in 1711. Obviously, he had multifarious interests. If your ancestors are from Quebec, there is a good chance he may be your ancestor. Finally, Daussy de Saint-Michel, back in France, had to pursue his military career. Let's bet that as a brave lieutenant, his banishment did not prevent him from taking up the charge with other soldiers.

02

02 The emergence of a homosexual subculture, in Montreal and other regions (1886-1892)

By the end of the 19th century, a number of areas of Montreal had acquired reputations as homosexual meeting places. A news article in La Presse titled ‘L’association nocture’ (The Nocturnal Association) graphically describes what happens at Champ-de-Mars, located behind City hall and the courthouse. As its name suggests, the Champ-de-Mars was a parade ground where public celebrations were held during the day, but it was also a fashionable place for evening strolls. What ensued at night, that is, men flirting with each other among the poplars that lined it, provides our earliest available evidence for gay social life in the city. Unfortunately, the article recounts the arrest of Clovis Villeneuve, who was ambushed through police entrapment, a despicable police practice still in use today.

Another meeting place for homosexuals, the Île Sainte-Hélène park, was established in the 1870s, next to the military garrison and the private Montreal Swimming Club. During the summer months, it was served by passenger ferries crossing the river to Longueuil from a wharf near the Victoria Pier. The five minute ride cost ten cents each way. Contemporary wood engravings of the park show Montrealers strolling, picnicking, playing games such as croquet, and conversing with soldiers from the Fort. But like the sheds in the Port and the steamships in the harbour, the island seems to have been the site of other forms of recreation... Two visitors during the summer of 1891, thirty year old William Cooney, and William Robinson, aged nineteen, were observed by Officer Ovide Tessier engaging in what he described as grossly indecent behaviour. They were sentenced respectively to six and nine months imprisonment with hard labour, and to whippings at regular intervals throughout their time in jail.

It is not only in large cities like Montreal that homosexuals were finding meeting places, be they cafés, bars or public parks. In 1892, a terrible scandal overwhelmed the small city of Saint-John (today called Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu). Following the denunciation by a priest of a group oddly called the “Club des manches de ligne” (The Fishing-Rod Handles Club), whose members had “unnatural” practices, the city’s mayor hired a Montreal detective agency to entrap the culprits. Four of them were subsequently accused of “indecent assault” and arrested, even if one of them was caught in Montreal where he tried to escape by the morning train. Upon his return on that very night, three hundred townsmen were waiting at the train station to lynch him, but luckily his police escort succeeded in protecting him. Following their release after the payment of a hefty bail, the four companions were seized, whipped in the public square, and finally chased out of the city by a hostile populace that did not appreciate that the scandal crossed the borders and found itself on the front page of the New York Times.

It is not only in large cities like Montreal that homosexuals were finding meeting places, be they cafés, bars or public parks. In 1892, a terrible scandal overwhelmed the small city of Saint-John (today called Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu). Following the denunciation by a priest of a group oddly called the “Club des manches de ligne” (The Fishing-Rod Handles Club), whose members had “unnatural” practices, the city’s mayor hired a Montreal detective agency to entrap the culprits. Four of them were subsequently accused of “indecent assault” and arrested, even if one of them was caught in Montreal where he tried to escape by the morning train. Upon his return on that very night, three hundred townsmen were waiting at the train station to lynch him, but luckily his police escort succeeded in protecting him. Following their release after the payment of a hefty bail, the four companions were seized, whipped in the public square, and finally chased out of the city by a hostile populace that did not appreciate that the scandal crossed the borders and found itself on the front page of the New York Times.

03

03 Dr Geoffrion’s Club (1908)

The extent of Quebec’s homosexual subculture at the turn of the twentieth century is revealed by the press coverage and the voluminous criminal records regarding Doctor Ulric Geoffrion and his friends. This forty year old physician had his practice in what was then called the “East End” of the city, more precisely at 1219 St-Catherine street East, in the block between Parthenais and Fullum streets. He opened his door to a large number of poor “young folks” (ready to money their services) and well to do (or not so well to do) gentlemen. In his meeting place or “club where men had fun with men”, one could breathe an atmosphere of incredible freedom. One could candidly inquire about someone’s sexual stamina, as shown by this conversation reported by the police: “…someone asked the doctor if he had a ‘beautiful one’ tonight. The doctor felt himself up and said: ‘No, not tonight.’ Someone else said: ‘Yesterday, you had one this size (the witness shows his arm) and it was almost impossible to take it in our mouths.’” Acts often followed words, as a curtained-off room with a bed allowed the regulars to “suck” and “jerk” each other; those who were using this room were said to be “on duty”. There were even initiation rites, as indicated by requests of some members for the doctor to perform what they called “the ceremony” on newcomers.

PMore fascinating than the freedom of speech and action was the solidarity of the members of this club. Below the surface of the “camp” humour that expressed itself in their calling each other “sister” or “my sister” lay a genuine feeling of fraternity (or “sorority”) that even extended to “sisters” who came from afar. Unfortunately this desire to help and support each other would be Doctor Geoffrion’s undoing when it was tapped by a so-called “sister” from Quebec City. For “Sister Trudeau”, to whom a member of the club promised a job at the Canadian Pacific Railway, turned out to be Constable Arthur Gagnon. His testimony would prove as damning as that of a sixteen year old prostitute, Albert Bonin. Police had followed the latter to his home and had denounced him to his father. His first impulse had been to run away from home to alert Doctor Geoffrion, but whether he was later intimidated by police or submitted to his father’s authority, he soon spilled the beans. Sadly for him, his collaboration did not pay off and he was condemned “to be imprisoned and kept at hard labor in the certified Reformatory School of Montreal during three years.”

The other accused men got off lightly with fines ranging from $50 to $500 and orders to keep the peace, except for Doctor Geoffrion, whom the judge perceived as a corruptor of youths and an “incurable man… more dangerous than if he were plague-ridden.” The court was merciless and condemned him to be imprisoned for fifteen years at the St-Vincent-de-Paul penitentiary.

These homosexuals were the victims of a concerted effort by the authorities, who were already affecting “special officers” to spy on and destroy the “clubs”. It is not surprising to find at the head of this police force none other than Chief Detective Carpenter, the same man who sixteen years before, in 1892, had presided over the infiltration and dismantlement of the “club des manches de ligne” (“Fishing-Rod Handles Club”) in St-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

The other accused men got off lightly with fines ranging from $50 to $500 and orders to keep the peace, except for Doctor Geoffrion, whom the judge perceived as a corruptor of youths and an “incurable man… more dangerous than if he were plague-ridden.” The court was merciless and condemned him to be imprisoned for fifteen years at the St-Vincent-de-Paul penitentiary.

These homosexuals were the victims of a concerted effort by the authorities, who were already affecting “special officers” to spy on and destroy the “clubs”. It is not surprising to find at the head of this police force none other than Chief Detective Carpenter, the same man who sixteen years before, in 1892, had presided over the infiltration and dismantlement of the “club des manches de ligne” (“Fishing-Rod Handles Club”) in St-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

04

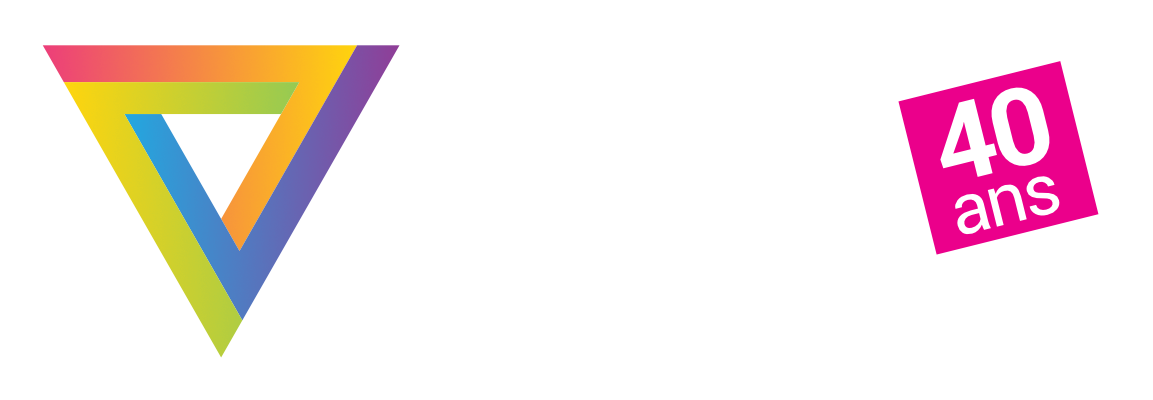

04 Gay Liberation Front (1971)

In the wake of the counter culture and the mobilization of women, blacks and youth in the 1960s, the gay liberation movement erupted with the riots at the Stonewall Inn in New York City in June 1969 (one day after Canada's Omnibus Bill decriminalized homosexual activity between two adults in private). The earlier homophile movement was quickly replaced by more militant groups which spread throughout North America in the next few years.

In Montreal, the magazine Mainmise spearheaded the diffusion of counter-cultural ideas, so it was not surprising that it was in its pages that gays published the call for a gay group. The Front de libération homosexuel (FLH) began in the spring of 1971 and soon obtained an office on rue St-Denis where gays could drop in and talk, take part in group discussions and write comments in the log book. During the following year they organized the city's first gay dances. In June 1972 the FLH moved into a larger space at the corner of Sanguinet and Ste-Catherine. Unfortunately, the leaders failed to obtain a liquor permit for their housewarming party and 40 members were taken to police headquarters after a raid. The climate of fear was still strong enough for these arrests to kill the group, leading to a two year eclipse of the francophone gay movement.

Despite this, Mainmise continued to include several articles with gay content. Moreover, in 1973, the bookstore L'Androgyne opened to cater to a gay and lesbian customer base. In 1977, the “Association pour les droits des gais du Québec” (ADGQ) (Association for the rights of gays in Quebec) was founded (it later became the “Association pour les droits des gais et des lesbiennes du Québec” (ADGLQ) (Association for the rights of gays and lesbians of Quebec), and took over the political advocacy for gay and lesbian rights. These organizations have now disappeared, but they have been replaced by a host of other more militant and advocacy organisations.

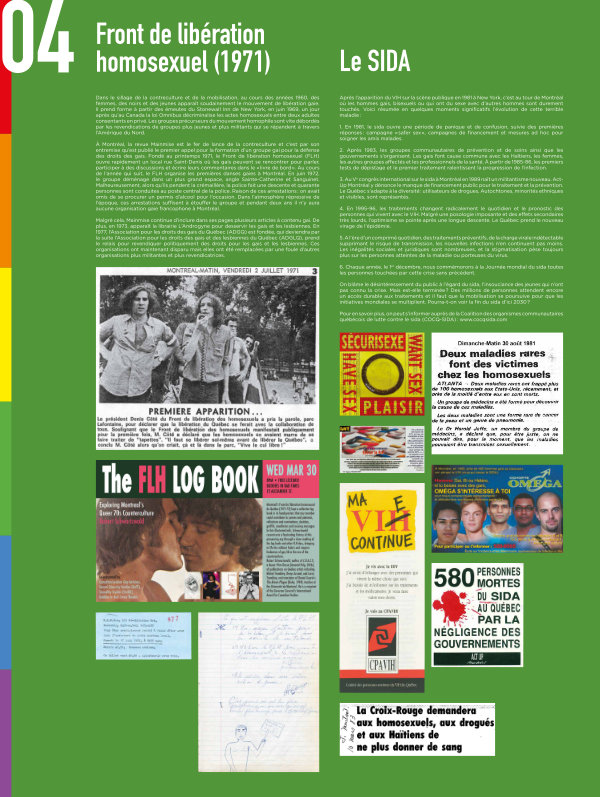

AIDS

After the appearance of HIV in the public sphere in 1981 in New York, it was then Montreal's turn, where gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men are heavily impacted. Here is a summary of the evolution of this terrible disease in a few significant moments:

For more information, contact the Coalition des organismes communautaires québécois de lutte contre le sida (COCQ-SIDA) (Coalition of community organisations in the fight against AIDS in Quebec): www.cocqsida.com (resource only available in French)

Despite this, Mainmise continued to include several articles with gay content. Moreover, in 1973, the bookstore L'Androgyne opened to cater to a gay and lesbian customer base. In 1977, the “Association pour les droits des gais du Québec” (ADGQ) (Association for the rights of gays in Quebec) was founded (it later became the “Association pour les droits des gais et des lesbiennes du Québec” (ADGLQ) (Association for the rights of gays and lesbians of Quebec), and took over the political advocacy for gay and lesbian rights. These organizations have now disappeared, but they have been replaced by a host of other more militant and advocacy organisations.

AIDS

After the appearance of HIV in the public sphere in 1981 in New York, it was then Montreal's turn, where gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men are heavily impacted. Here is a summary of the evolution of this terrible disease in a few significant moments:

- In 1981, AIDS ushered in a period of panic and confusion, followed by the first responses: a "safer sex" campaign, fundraising campaigns and ad hoc measures to care for sick friends.

- After 1983, community prevention and care groups, as well as governments began to organize. Gays made common cause with Haitians, women, other affected groups and health professionals. By 1985-86, the first tests and treatment slowed down the progression of the infection.

- At the 5th International AIDS Conference in Montreal in 1989, a new type of activism was born. Act-Up Montreal denounced the lack of public funding for treatment and prevention. Quebec adapted to diversity: drug users, Indigenous folks, ethnic and visible minorities were now represented.

- In 1995-96, treatments radically changed the daily lives and prognosis of people living with HIV. In spite of the large dosage and the very heavy side effects, optimism emerged after a long descent. Quebec took a new turn in the epidemic.

- In the era of daily pills, of preventive treatments, of undetectable viral loads eliminating the risk of transmission, new infections nonetheless continue. Social and legal inequalities are numerous, and the stigma of being infected or carrying the virus is ever increasing.

- Each year on World AIDS Day, December 1st, we commemorate all those affected by this unprecedented crisis.

For more information, contact the Coalition des organismes communautaires québécois de lutte contre le sida (COCQ-SIDA) (Coalition of community organisations in the fight against AIDS in Quebec): www.cocqsida.com (resource only available in French)

05

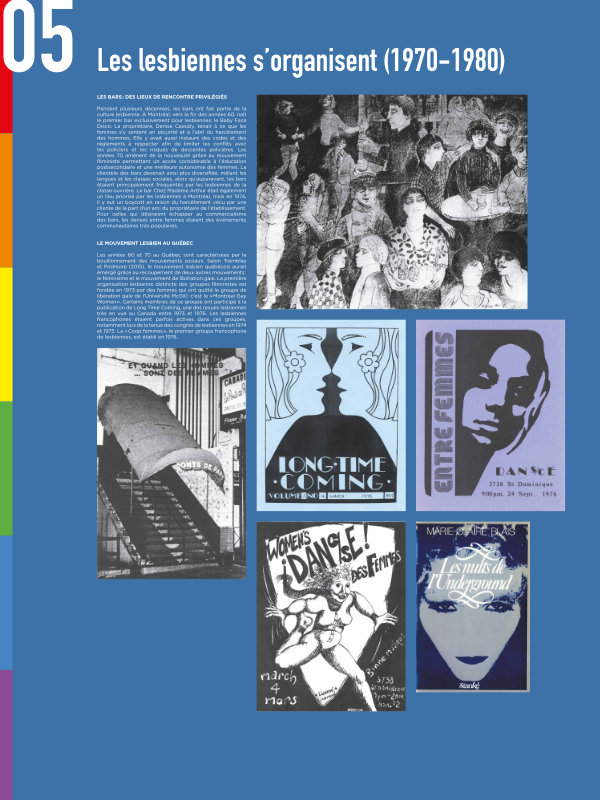

05 Lesbians mobilise (1970-1980)

BARS: PRIVILEGED MEETING PLACES

For many decades, bars have been part of lesbian culture. In Montreal, in the late 1960s, the first lesbian-only bar, Baby Face Disco, opened. The owner, Denise Cassidy, wanted women to feel safe and free from harassment by men. She also established codes and rules to be respected in order to limit conflicts with the police and the risk of police raids. The 1970's brought new developments within the feminist movement allowing considerable access to post-secondary education and greater autonomy for women. The customer base of the bars became more diverse, languages and social classes mixing, whereas previously the bars were mainly frequented by working class lesbians. The bar Chez Madame Arthur was also a popular place for lesbians in Montreal, but in 1974 it faced a boycott because of the harassment of a client by a friend of the owner. For those who wished to avoid the commercialism of bars, community organized dances were popular events.

THE LESBIAN MOVEMENT IN QUEBEC

The 1960s and 1970s in Quebec were characterized by the stirrings of social movements. According to Tremblay and Podmore (2015), the Quebec lesbian movement emerged through the intersection of two other movements: feminism and the gay liberation movement. Early lesbian organizing, outside of feminist groups, followed the departure of women from the gay liberation group at McGill University in early 1973 to set up Montreal Gay Women. Some members of this group were involved in the publication of Long Time Coming, one of Canada's major lesbian magazines between 1973 and 1976. Francophone lesbians were active in these groups to some extent, especially in the lesbian conferences held here in 1974 and 1975. Coop Femmes, the first francophone group for lesbians, began in 1976.

06

06 WHAT HAVE THE LESBIANS BECOME? (1980 to today

The more radical second wave of the feminist movement influenced the lesbian community in the 1980s. Lesbian bars were owned by women and accessible only to women. Three bars were well known during these years in the city of Montreal: Labyris, Lilith and L'Exit. Several lesbian periodicals were born, including entirely francophone ones: Amazones d'hier (Yesterday's Amazonians), lesbiennes d'aujourd'hui (1982) (Today's Lesbians), Ça s'attrape (1982) (It Spreads) and Treize (1984) (Thirteen). The 90's also saw the birth of lesbian groups. We can name among others the Réseau des lesbiennes du Québec (RLQ) (Lesbian Network of Quebec) founded in 1996. The RLQ, which is still active, aims to provide a voice for Quebec lesbians in the public space by taking part in numerous social and political issues, particularly regarding gender equality. The organisation Lez Spread the Word, born in 2011, is very active today and aims to produce content by and for lesbian women while giving them positive role models. LSTW launched its own web series Féminin/Féminin (Feminine/Feminine) in 2014 as well as the first issue of its magazine in 2016. This organisation also creates events seeking to bring women in the LGBTQ2+ community together such as the famous "Où sont les femmes?" (Where are the Women?).

WHERE ARE THE LESBIANS?

Lesbians tend to be invisibilised within Quebec society and sometimes even within the LGBTQ2+ community itself. In addition, the city of Montreal currently has no lesbian bars, as the Drugstore closed in 2014, as did the Royal Phoenix. This makes initiatives of organisations like Lez Spread the Word all the more relevant to enrich Quebec's lesbian culture and provide meeting places. Without a doubt, LSTW is a solution to the invisibility of women in the LGBTQ2+ community. Let's also note that the first lesbian walk in Quebec took place on August 14th, 2012.

07

07 Trans realities: an ongoing struggle

The fight for trans rights is much more recent, as is the fight against transphobia and the concern for trans children. The first major organisation for trans people in Quebec was founded in 1980. It is the organisation Aide aux trans du Québec (Support for Trans folks of Quebec) founded by Marie-Marcelle Godbout. More than a helpline, the ATQ organises many activities for the trans community, meetings to support the families of trans people by answering their questions, etc. Another very important organisation for the community is the Action Santé Travesti(e)s et Transsexuel(le)s du Québec (ASST(e)Q) (Health Action Transvestites and Transexuals of Quebec) founded in 1998. ASST(e)Q aims to promote the health and well-being of trans people and advocates, among other things, for better access to health services that meet the specific needs of the community. Since the beginning of the 2000s, trans realities have become more and more visible in the media. Today, many television series and features address this issue in order to demystify these realities. The television program Je suis trans (I Am Trans), broadcasted on the channel MOI ET CIE, is an example.

IMPORTANT RECENT DATES AND EVENTS:

- June 10th 2016: the Quebec government modifies the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms to prohibit discrimination based on "gender identity or expression".

- June 19th 2016: the federal government incorporates this prohibition of discrimination into the Canadian Human Rights Act.

- 5November 5th 2016: A first trans mayor is elected in Quebec. Her name is Julie Lemieux, mayor of the town of the Très-Saint-Rédempteur

Queer Movemen

LThe queer movement is multidimensional and inclusive. It includes people from all sexual and gender minorities who do not identify with the heterosexual and cisgender normative model that prevails in society. From the English word for "strange" or "weird", the word was used as early as the 19th century in Anglo-Saxon countries to stigmatize sexual deviance, especially relationships between partners of the same sex.

An example of community empowerment, the term was transformed in the 1980s into a positive and emancipatory term. The movement has its intellectual roots in the queer theory that emerged in American and British universities under the influence of materialist and lesbian feminism, as well as postcolonial theory since the 1970s. Queer thinkers (Ferguson, Puar, Duggan, Han, Sedgwick, and Butler) emphasize the influence of the surrounding culture on the expression and construction of gender and sexuality, and the roles and identities associated with them. Queer theory opposes normativity and the rigidity of male/female or homo/heterosexual binarisms. From the 1990s onwards, radical queer differentiated itself from queer theory - considered too academic - and moved closer to anarchism, Marxism and radical feminism. Denouncing what it perceives as a conservative liberal turn in the LGBTQIA2 community, queer activism seeks to be intersectional and inclusive, with the goal of affirming the expression of otherwise often-marginalized members, namely racialized and/or trans people.

In Montreal, well rooted at McGill (Queer McGill) and Concordia (Queer Concordia), the movement also gave birth to several groups denouncing the commercialisation and discriminations present in the LGBTQIA2 community (sexism, heterosexism, homonormativity, classism, ageism, serophobia, racism). Groups such as the P!nk Bloc (2000), the Pink Panthers and QueerÉaction (2002 to 2007), Qteam and Radical Queer Anti-Capitalist Ass (2004 to 2007), the Radical Queer Collective, or PolitiQ (2009). The queer movement was also at the root of community initiatives such as Projet10 (2009), which works to promote the well-being of LGBTQIA2 youth, as well as Plan Q, which offers workshops to CEGEPs and universities to raise awareness about the fight against LGBTphobia.

As an alternative to the traditional LGBT movement, queer movement also fosters new events, as well as gathering and meeting places, mostly located outside the Village. A new spatiality which unfolds in the Mile-End, Rosemont or Hochelaga : the Pervers/Cité festival (2006), the book fair Queer Between the Covers (2007), the Radical Queer Week (2009 to 2016), the monthly queer dance Faggity Ass Friday (2007 to 2015), the inclusive lesbian evening "Où sont les femmes?" of Lez Spread the Word (2012), the gay-queer night Mec Plus Ultra (2008), the Montreal Queer Slowdance and Queer Tango at the Mainline Theatre are examples, not to mention the creation of new queer bars - sometimes mixed - such as the Royal Phoenix (closed in 2015), the Notre-Dame des Quilles, the Renard, or the Alexandraplatz.

08

08 Arc-en-ciel d’Afrique

In 2004, when the Quebec government legalized same-sex marriage, LGBT people from Black communities were still invisible on the gay scene and in the fight against homophobia. In order to allow LGBT people of African and Caribbean origins to enjoy the rights and freedoms granted to them in Quebec, Solange Musanganya, Didier Rwigamba and Luc Doray created the organisation Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique on November 30th 2004.

Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique was a non-profit community organisation that worked towards the integration and fulfillment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and transsexual (LGBT) people from the African and Caribbean communities, as well as their families and their friends in Quebec. To achieve these goals, the organisation had the following mandates:

Throughout its existence, Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique has contributed to improving the lives of thousands of LGBT people from Black communities, to promoting their rights, and also to increasing the visibility of these communities by making the public aware of their specific intersectional issues.

Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique took part in the Pride March for the first time in 2006, then consecutively from 2009 to 2017. In 2014, Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique created Fierté Afropride, a series of events open to the general public to highlight the presence of LGBT people from African and Caribbean communities during Montreal's Pride Week.

In 2009, Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique founded the African and Caribbean LGBT film festival known today as Massimadi: Afro LGBTQ+ Film and Arts Festival. Arc-en ciel d'Afrique ended its activities in the spring of 2018. However, its legacy continues through the Massimadi festival, which will present its 12th edition in February 2020 under the aegis of the Massimadi Foundation created in August 2018.

Two-Spirit

The Two-Spirit umbrella term is rooted in traditions of Indigenous peoples. It is a concept that refers to an individual with a dual identity, that is to say both female and male, and that reflects the tradition of sexual and gender diversity in Indigenous cultures. Long buried in the ancestral memory of Indigenous peoples, two-spiritedness has reappeared in the last fifty years among LGBTQ Indigenous folks who want to reclaim their traditions. In the wake of sexual and gender diversity, the two-spirit umbrella term allows individuals to find a balance in the roles and behaviors of everyday life. There is also a resurgence of artistic creativity among First Nations two-spirited people.

Traditionally, the Two-Spirit identity gave individuals a supernatural ability that allowed them to play an important role in their community. Many were shamans, healers, storytellers or advisors to chiefs and elders because they could, through dreams or visions, make contact with the spirits of nature. Their great knowledge in singing, dancing and the art of oratory was valued. Their advice and insight were highly respected in the governance of their people. Among many Indigenous peoples, Two-Spirit identity was accepted in both men and women. The two-spirited individual had the physical attributes of one sex but the behaviour of the other.

Everything changed with the arrival of European explorers and missionaries. Astonishment was soon followed by repugnance and disgust in front of such individuals. Since the colonisers' had no term for two-spirited people, the word "berdache" (used in France to refer to a passive or effeminate boy or young man who had sex with men) was applied. However, early on in the Americas, for lack of other words on the colonisers’ part, the term came to designate any Indigenous man, regardless of age or social status, who had sex with other men. Two-spiritedness was thus reduced to male sexual deviance. The missionaries were the most virulent towards people who acted against nature and challenged the gender hierarchy. Thus, Father Louis Hennepin, a Franciscan missionary, wrote in 1683: “I saw a boy of about seventeen or eighteen years old who had dreamed that he was a girl, he had so much faith in that fact that he believed it to be true; he dresses like a girl, & does all the same tasks as the women.” Later he added: "They are shameless to the point of falling into the sin that is against nature. They have boys, to whom they give the appearance of girls, because they use them for this abominable purpose. These boys are occupied only with the works of women, and do not take part in Hunting or war." At the same time, the Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette, who accompanied the explorer Louis Joliet, found that such behaviours perverted the gender hierarchy and undermined "masculine perfection"!

Colonization, christianization and forced cultural assimilation (such as the residential school system) led to the disappearance of the recognition of Two-Spirit identities among Indigenous peoples. Today, two-spirited people continue to face sexual and gender discrimination even within their communities. Arc-en-ciel d’Afrique © Marcel

- To raise awareness in Quebec on the realities of LGBT people from African and Caribbean communities and to act in the prevention of STIs and HIV;

- To break the isolation of LGBT people from African and Caribbean communities;

- To promote the LGBT cultures of African and Caribbean communities.

Throughout its existence, Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique has contributed to improving the lives of thousands of LGBT people from Black communities, to promoting their rights, and also to increasing the visibility of these communities by making the public aware of their specific intersectional issues.

Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique took part in the Pride March for the first time in 2006, then consecutively from 2009 to 2017. In 2014, Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique created Fierté Afropride, a series of events open to the general public to highlight the presence of LGBT people from African and Caribbean communities during Montreal's Pride Week.

In 2009, Arc-en-ciel d'Afrique founded the African and Caribbean LGBT film festival known today as Massimadi: Afro LGBTQ+ Film and Arts Festival. Arc-en ciel d'Afrique ended its activities in the spring of 2018. However, its legacy continues through the Massimadi festival, which will present its 12th edition in February 2020 under the aegis of the Massimadi Foundation created in August 2018.

Two-Spirit

The Two-Spirit umbrella term is rooted in traditions of Indigenous peoples. It is a concept that refers to an individual with a dual identity, that is to say both female and male, and that reflects the tradition of sexual and gender diversity in Indigenous cultures. Long buried in the ancestral memory of Indigenous peoples, two-spiritedness has reappeared in the last fifty years among LGBTQ Indigenous folks who want to reclaim their traditions. In the wake of sexual and gender diversity, the two-spirit umbrella term allows individuals to find a balance in the roles and behaviors of everyday life. There is also a resurgence of artistic creativity among First Nations two-spirited people.

Traditionally, the Two-Spirit identity gave individuals a supernatural ability that allowed them to play an important role in their community. Many were shamans, healers, storytellers or advisors to chiefs and elders because they could, through dreams or visions, make contact with the spirits of nature. Their great knowledge in singing, dancing and the art of oratory was valued. Their advice and insight were highly respected in the governance of their people. Among many Indigenous peoples, Two-Spirit identity was accepted in both men and women. The two-spirited individual had the physical attributes of one sex but the behaviour of the other.

Everything changed with the arrival of European explorers and missionaries. Astonishment was soon followed by repugnance and disgust in front of such individuals. Since the colonisers' had no term for two-spirited people, the word "berdache" (used in France to refer to a passive or effeminate boy or young man who had sex with men) was applied. However, early on in the Americas, for lack of other words on the colonisers’ part, the term came to designate any Indigenous man, regardless of age or social status, who had sex with other men. Two-spiritedness was thus reduced to male sexual deviance. The missionaries were the most virulent towards people who acted against nature and challenged the gender hierarchy. Thus, Father Louis Hennepin, a Franciscan missionary, wrote in 1683: “I saw a boy of about seventeen or eighteen years old who had dreamed that he was a girl, he had so much faith in that fact that he believed it to be true; he dresses like a girl, & does all the same tasks as the women.” Later he added: "They are shameless to the point of falling into the sin that is against nature. They have boys, to whom they give the appearance of girls, because they use them for this abominable purpose. These boys are occupied only with the works of women, and do not take part in Hunting or war." At the same time, the Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette, who accompanied the explorer Louis Joliet, found that such behaviours perverted the gender hierarchy and undermined "masculine perfection"!

Colonization, christianization and forced cultural assimilation (such as the residential school system) led to the disappearance of the recognition of Two-Spirit identities among Indigenous peoples. Today, two-spirited people continue to face sexual and gender discrimination even within their communities. Arc-en-ciel d’Afrique © Marcel